| From | Portside Culture <[email protected]> |

| Subject | Farmers Sell Their Produce |

| Date | December 13, 2022 1:05 AM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

[The Southside Community Land Trust (SCLT) in Providence, Rhode

Island works to give immigrant farmers opportunities to sell what they

grow to wholesale markets. ]

[[link removed]]

PORTSIDE CULTURE

FARMERS SELL THEIR PRODUCE

[[link removed]]

Bridget Shirvell

September 25, 2022

Modern Farmer

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

_ The Southside Community Land Trust (SCLT) in Providence, Rhode

Island works to give immigrant farmers opportunities to sell what they

grow to wholesale markets. _

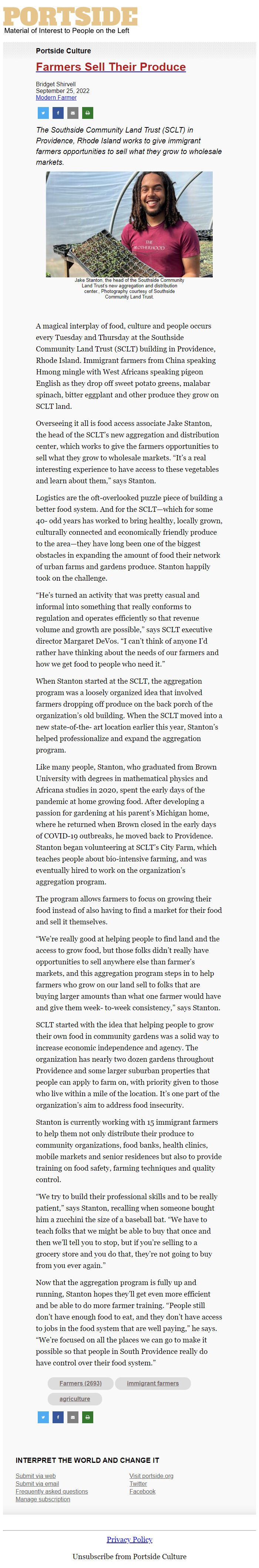

Jake Stanton, the head of the Southside Community Land Trust’s new

aggregation and distribution center., Photography courtesy of

Southside Community Land Trust.

A magical interplay of food, culture and people occurs every Tuesday

and Thursday at the Southside Community Land Trust (SCLT) building in

Providence, Rhode Island. Immigrant farmers from China speaking Hmong

mingle with West Africans speaking pigeon English as they drop off

sweet potato greens, malabar spinach, bitter eggplant and other

produce they grow on SCLT land.

Overseeing it all is food access associate Jake Stanton, the head of

the SCLT’s new aggregation and distribution center, which works to

give the farmers opportunities to sell what they grow to wholesale

markets. “It’s a real interesting experience to have access to

these vegetables and learn about them,” says Stanton.

Logistics are the oft-overlooked puzzle piece of building a better

food system. And for the SCLT—which for some 40- odd years has

worked to bring healthy, locally grown, culturally connected and

economically friendly produce to the area—they have long been one of

the biggest obstacles in expanding the amount of food their network of

urban farms and gardens produce. Stanton happily took on the

challenge.

“He’s turned an activity that was pretty casual and informal into

something that really conforms to regulation and operates efficiently

so that revenue volume and growth are possible,” says SCLT executive

director Margaret DeVos. “I can’t think of anyone I’d rather

have thinking about the needs of our farmers and how we get food to

people who need it.”

When Stanton started at the SCLT, the aggregation program was a

loosely organized idea that involved farmers dropping off produce on

the back porch of the organization’s old building. When the SCLT

moved into a new state-of-the- art location earlier this year,

Stanton’s helped professionalize and expand the aggregation program.

Like many people, Stanton, who graduated from Brown University with

degrees in mathematical physics and Africana studies in 2020, spent

the early days of the pandemic at home growing food. After developing

a passion for gardening at his parent’s Michigan home, where he

returned when Brown closed in the early days of COVID-19 outbreaks, he

moved back to Providence. Stanton began volunteering at SCLT’s City

Farm, which teaches people about bio-intensive farming, and was

eventually hired to work on the organization’s aggregation program.

The program allows farmers to focus on growing their food instead of

also having to find a market for their food and sell it themselves.

“We’re really good at helping people to find land and the access

to grow food, but those folks didn’t really have opportunities to

sell anywhere else than farmer’s markets, and this aggregation

program steps in to help farmers who grow on our land sell to folks

that are buying larger amounts than what one farmer would have and

give them week- to-week consistency,” says Stanton.

SCLT started with the idea that helping people to grow their own food

in community gardens was a solid way to increase economic independence

and agency. The organization has nearly two dozen gardens throughout

Providence and some larger suburban properties that people can apply

to farm on, with priority given to those who live within a mile of the

location. It’s one part of the organization’s aim to address food

insecurity.

Stanton is currently working with 15 immigrant farmers to help them

not only distribute their produce to community organizations, food

banks, health clinics, mobile markets and senior residences but also

to provide training on food safety, farming techniques and quality

control.

“We try to build their professional skills and to be really

patient,” says Stanton, recalling when someone bought him a zucchini

the size of a baseball bat. “We have to teach folks that we might be

able to buy that once and then we’ll tell you to stop, but if

you’re selling to a grocery store and you do that, they’re not

going to buy from you ever again.”

Now that the aggregation program is fully up and running, Stanton

hopes they’ll get even more efficient and be able to do more farmer

training. “People still don’t have enough food to eat, and they

don’t have access to jobs in the food system that are well

paying,” he says. “We’re focused on all the places we can go to

make it possible so that people in South Providence really do have

control over their food system.”

* Farmers (2693)

[[link removed]]

* immigrant farmers

[[link removed]]

* agriculture

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

INTERPRET THE WORLD AND CHANGE IT

Submit via web

[[link removed]]

Submit via email

Frequently asked questions

[[link removed]]

Manage subscription

[[link removed]]

Visit portside.org

[[link removed]]

Twitter [[link removed]]

Facebook [[link removed]]

########################################################################

[link removed]

To unsubscribe from the xxxxxx list, click the following link:

[link removed]

Island works to give immigrant farmers opportunities to sell what they

grow to wholesale markets. ]

[[link removed]]

PORTSIDE CULTURE

FARMERS SELL THEIR PRODUCE

[[link removed]]

Bridget Shirvell

September 25, 2022

Modern Farmer

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

_ The Southside Community Land Trust (SCLT) in Providence, Rhode

Island works to give immigrant farmers opportunities to sell what they

grow to wholesale markets. _

Jake Stanton, the head of the Southside Community Land Trust’s new

aggregation and distribution center., Photography courtesy of

Southside Community Land Trust.

A magical interplay of food, culture and people occurs every Tuesday

and Thursday at the Southside Community Land Trust (SCLT) building in

Providence, Rhode Island. Immigrant farmers from China speaking Hmong

mingle with West Africans speaking pigeon English as they drop off

sweet potato greens, malabar spinach, bitter eggplant and other

produce they grow on SCLT land.

Overseeing it all is food access associate Jake Stanton, the head of

the SCLT’s new aggregation and distribution center, which works to

give the farmers opportunities to sell what they grow to wholesale

markets. “It’s a real interesting experience to have access to

these vegetables and learn about them,” says Stanton.

Logistics are the oft-overlooked puzzle piece of building a better

food system. And for the SCLT—which for some 40- odd years has

worked to bring healthy, locally grown, culturally connected and

economically friendly produce to the area—they have long been one of

the biggest obstacles in expanding the amount of food their network of

urban farms and gardens produce. Stanton happily took on the

challenge.

“He’s turned an activity that was pretty casual and informal into

something that really conforms to regulation and operates efficiently

so that revenue volume and growth are possible,” says SCLT executive

director Margaret DeVos. “I can’t think of anyone I’d rather

have thinking about the needs of our farmers and how we get food to

people who need it.”

When Stanton started at the SCLT, the aggregation program was a

loosely organized idea that involved farmers dropping off produce on

the back porch of the organization’s old building. When the SCLT

moved into a new state-of-the- art location earlier this year,

Stanton’s helped professionalize and expand the aggregation program.

Like many people, Stanton, who graduated from Brown University with

degrees in mathematical physics and Africana studies in 2020, spent

the early days of the pandemic at home growing food. After developing

a passion for gardening at his parent’s Michigan home, where he

returned when Brown closed in the early days of COVID-19 outbreaks, he

moved back to Providence. Stanton began volunteering at SCLT’s City

Farm, which teaches people about bio-intensive farming, and was

eventually hired to work on the organization’s aggregation program.

The program allows farmers to focus on growing their food instead of

also having to find a market for their food and sell it themselves.

“We’re really good at helping people to find land and the access

to grow food, but those folks didn’t really have opportunities to

sell anywhere else than farmer’s markets, and this aggregation

program steps in to help farmers who grow on our land sell to folks

that are buying larger amounts than what one farmer would have and

give them week- to-week consistency,” says Stanton.

SCLT started with the idea that helping people to grow their own food

in community gardens was a solid way to increase economic independence

and agency. The organization has nearly two dozen gardens throughout

Providence and some larger suburban properties that people can apply

to farm on, with priority given to those who live within a mile of the

location. It’s one part of the organization’s aim to address food

insecurity.

Stanton is currently working with 15 immigrant farmers to help them

not only distribute their produce to community organizations, food

banks, health clinics, mobile markets and senior residences but also

to provide training on food safety, farming techniques and quality

control.

“We try to build their professional skills and to be really

patient,” says Stanton, recalling when someone bought him a zucchini

the size of a baseball bat. “We have to teach folks that we might be

able to buy that once and then we’ll tell you to stop, but if

you’re selling to a grocery store and you do that, they’re not

going to buy from you ever again.”

Now that the aggregation program is fully up and running, Stanton

hopes they’ll get even more efficient and be able to do more farmer

training. “People still don’t have enough food to eat, and they

don’t have access to jobs in the food system that are well

paying,” he says. “We’re focused on all the places we can go to

make it possible so that people in South Providence really do have

control over their food system.”

* Farmers (2693)

[[link removed]]

* immigrant farmers

[[link removed]]

* agriculture

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

INTERPRET THE WORLD AND CHANGE IT

Submit via web

[[link removed]]

Submit via email

Frequently asked questions

[[link removed]]

Manage subscription

[[link removed]]

Visit portside.org

[[link removed]]

Twitter [[link removed]]

Facebook [[link removed]]

########################################################################

[link removed]

To unsubscribe from the xxxxxx list, click the following link:

[link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Portside

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- L-Soft LISTSERV