Chickens Are NOT Cannibals

By Karen Davis, PhD, President of United Poultry Concerns

Weaver Brothers Egg Farm in Versailles, Ohio. Photo by: Mercy for Animals.

Animal people must never call chickens “cannibals,” or suggest that they are naturally prone to “cannibalism” – the practice of eating the flesh of one’s own species. Avoiding this false and pejorative attribution to chickens is an important part of liberating our language from “factory-farm-speak.” That said, poultry researchers from the early days of factory farming in the 20th century identified root causes of what may appear in some captive chickens to be an innately driven “cannibalism” comprising pecking behaviors that are, in fact, the chickens’ response to human-imposed frustrations and deprivations. “Cannibalism” is an anthropomorphically-induced pathology in chickens. It is not normal chicken behavior, and since “cannibalism” sounds odious to most people, we must never use it in speaking of chickens except to dispel the notion that they are “cannibalistic” by nature, which they are not.

What conditions can cause “cannibalism” in chickens?

Feral chickens spend about half their time foraging and feeding, and

make an estimated 14,000-15,000 pecks at food items and other objects

in the course of a day.

– Bell and Weaver, 73.

Cannibalism develops either as a result of misdirected ground pecking or is

associated with [misdirected] dust bathing behaviour.

– Philip C Glatz, Beak Trimming, 11.

In cages, feather pecking occurs particularly during the afternoon when

hens have finished feeding and laying eggs, and have little else to do.

– Christine Nicol and Marian Stamp Dawkins, “Homes fit for

hens,” New Scientist, 50.

According to North and Bell, “When birds are given limited space, as in cages, there is a tendency for many to become cannibalistic” (309). This behavior is caused by the abnormal restriction of the normal span of activities in ground-ranging species of birds in situations in which they are squeezed together and prevented from exercising their natural exploratory, food-gathering, dustbathing, and social impulses. It includes vent picking, feather pulling, toe picking, head picking and in some cases consumption of flesh. Pecking in chickens is a genetic behavior developed through evolution that enables them not only to defend themselves, but to forage, for as chicken specialist Lesley J. Rogers states, “birds must use the beak to explore the environment, much as we use our hands” (1995, 96).

Poultry researchers attribute abnormal pecking behavior to a variety of interactive causes including artificial lighting intensities and durations to force overproduction of eggs. In addition, chickens may be driven to peck and pull the feathers of cagemates in order to obtain nutrients they would find on range but cannot obtain in fixed commercial rations. Mash and pellets exacerbate the problem because the birds cannot select specific nutritional components, and they fill up quickly leaving them with nothing to occupy their beaks and their time (Rogers 1995, 219; Bell and Weaver, 86, 239).

Caged chickens, especially, may be driven to peck at each other as a result of their inability to dustbathe. Studies show that hens deprived of dustbathing material suffer from “an abnormal development of the perceptual mechanism responsible for the detection of dust for dustbathing.” Without any form of loose, earth-like material, chickens “are more likely to come to accept feathers as dust” (Vestergaard 1993, 1127, 1138).

In addition, research shows that fear is not only a result of the pecking of cagemates, but also a cause of it. According to Klaus Vestergaard, “the peckers are the fearful birds, and the more they peck the more fearful they are. This finding emphasizes abnormal behavior in the evaluation of well-being in animals who have no obvious physical signs of suffering” (1993, 1138).

A poultry researcher learned the importance of pecking when he designed a method of feeding chicks by pumping slurry directly into their necks. He wrote, “The slurry that was fed had the right amount of both food and water, so that the chicks did not need to peck to prehend either feed or water. And the end of all that research (with Dr. Graham Sterritt, an NIH Fellow) for 5-6 years was that chicks peck independently of whether or not they need to peck in order to eat. I still cannot believe all of the money spent to study that” (Kienholz 1990).

A poultry breeder recalls the emergence of cannibalism in the 1920s. “When I was a senior, the University [of New Hampshire] hired a new laboratory man from the West – Dr. Gildow. He recommended using wire platforms, which let the droppings fall through the floor. This interrupted multiplication of the coccidia oocysts. But it led to a completely new problem – cannibalism – and after a year or so wire platforms were out” (Coleman 1976, 51). Out, that is, for “broiler” chickens, but not for egg-laying hens.

A poultry nutritionist recalls that when high energy feeds “were not adequately fortified with other nutrients, especially protein, they caused a new problem – cannibalism and feather picking. The problem was aggravated by excessive use of supplementary light. . . . Debeaking helped to control cannibalism and soon became a standard practice” (Day, 142).

REFERENCES

Bell, Donald D., and William D. Weaver, Jr., eds. 2002. Commercial Chicken Meat and Egg Production, 5th ed. Norwell, Mass: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Coleman, George E., Jr. 1976. One Man’s Recollections Over 50 Years. Broiler Industry July: 48-60.

Day, Elbert J. 1976. Broiler Nutrition: yesterday today tomorrow. Broiler Industry July: 140-143.

Glatz, Philip C., ed. 2005. Beak Trimming. Nottingham, U.K.: Nottingham University Press.

Kienholz, Eldon W. 1990. Letter to Donald J. Barnes, 13 February.

Nicol, Christine, and Marian Stamp Dawkins. 1990. Homes fit for hens. New Scientist 17 (March): 46-51.

Rogers, Lesley J. 1995. The Development of Brain and Behaviour in the Chicken: Oxon, UK: CAB International.

Vestergaard, Klaus. 1993. Feather pecking and chronic fear in groups of red jungle fowl: their relations to dustbathing, rearing environment and social status. Animal Behaviour 45: 1127-1140.

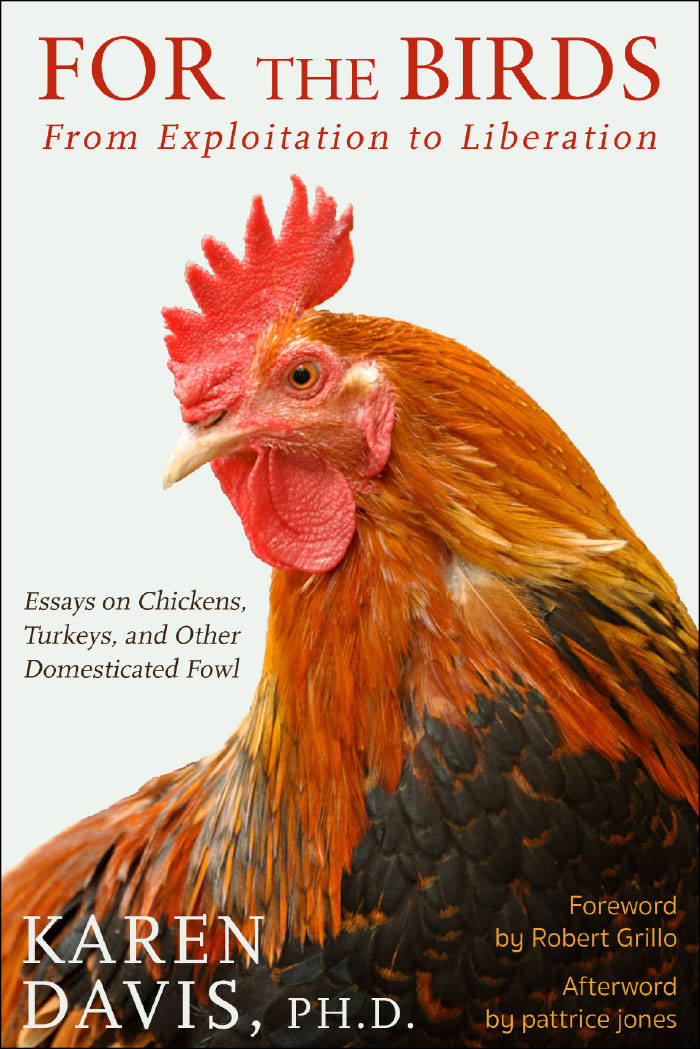

KAREN DAVIS, PhD is the President and Founder of United Poultry Concerns, a nonprofit organization that promotes the compassionate and respectful treatment of domestic fowl including a sanctuary for chickens in Virginia. Inducted into the National Animal Rights Hall of Fame for Outstanding Contributions to Animal Liberation, Karen is the author of numerous books, essays, articles and campaigns. Her latest book is For the Birds: From Exploitation to Liberation: Essays on Chickens, Turkeys, and Other Domesticated Fowl (Lantern Books, 2019).

| Order Now! |

Don't just switch from beef to chicken. Go Vegan.

www.UPC-online.org