| From | Michigan DNR <[email protected]> |

| Subject | Showcasing the DNR: Protecting Michigan’s bats |

| Date | January 22, 2026 6:33 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Michigan’s ecologically and economically important bat populations are facing serious challenges.

Share or view as webpage [ [link removed] ] | Update preferences [ [link removed] ]

DNR banner [ [link removed] ]

"Showcasing the DNR"

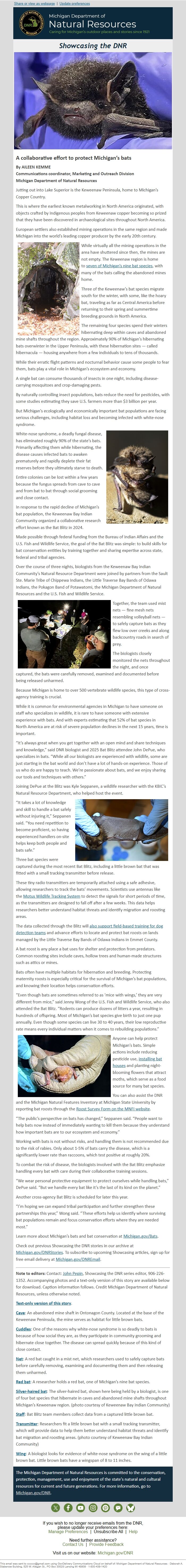

Close-up of silver-haired bat held by gloved hands

*A collaborative effort to protect Michigan’s bats*

*By AILEEN KEMME*

*Communications coordinator, Marketing and Outreach Division*

*Michigan Department of Natural Resources*

Jutting out into Lake Superior is the Keweenaw Peninsula, home to Michigan’s Copper Country.

This is where the earliest known metalworking in North America originated, with objects crafted by Indigenous peoples from Keweenaw copper becoming so prized that they have been discovered in archaeological sites throughout North America.

European settlers also established mining operations in the same region and made Michigan into the world’s leading copper producer by the early 20th century.

opening of an abandoned mine shaft

While virtually all the mining operations in the area have shuttered since then, the mines are not empty. The Keweenaw region is home to seven of Michigan’s nine bat species [ [link removed] ], with many of the bats calling the abandoned mines home.

Three of the Keweenaw’s bat species migrate south for the winter, with some, like the hoary bat, traveling as far as Central America before returning to their spring and summertime breeding grounds in North America.

The remaining four species spend their winters hibernating deep within caves and abandoned mine shafts throughout the region. Approximately 90% of Michigan’s hibernating bats overwinter in the Upper Peninsula, with these hibernation sites — called hibernacula" "— housing anywhere from a few individuals to tens of thousands.

While their erratic flight patterns and nocturnal behavior cause some people to fear them, bats play a vital role in Michigan’s ecosystem and economy.

A single bat can consume thousands of insects in one night, including disease-carrying mosquitoes and crop-damaging pests.

By naturally controlling insect populations, bats reduce the need for pesticides, with some studies estimating they save U.S. farmers more than $3 billion per year.

But Michigan’s ecologically and economically important bat populations are facing serious challenges, including habitat loss and becoming infected with white-nose syndrome.

group of bats cuddled together in a cave

White-nose syndrome, a deadly fungal disease, has eliminated roughly 90% of the state’s bats. Primarily affecting them while hibernating, the disease causes infected bats to awaken prematurely and rapidly deplete their fat reserves before they ultimately starve to death.

Entire colonies can be lost within a few years because the fungus spreads from cave to cave and from bat to bat through social grooming and close contact.

In response to the rapid decline of Michigan’s bat population, the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community organized a collaborative research effort known as the Bat Blitz in 2024.

Made possible through federal funding from the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the goal of the Bat Blitz was simple: to build skills for bat conservation entities by training together and sharing expertise across state, federal and tribal agencies.

Over the course of three nights, biologists from the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community’s Natural Resource Department were joined by partners from the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians, the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi, the Michigan Department of Natural Resources and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Bat Blitz team members collect data from a captured little brown bat.

Together, the team used mist nets — fine mesh nets resembling volleyball nets — to safely capture bats as they flew low over creeks and along backcountry roads in search of prey.

The biologists closely monitored the nets throughout the night, and once captured, the bats were carefully removed, examined and documented before being released unharmed.

Because Michigan is home to over 500 vertebrate wildlife species, this type of cross-agency training is crucial.

While it is common for environmental agencies in Michigan to have someone on staff who specializes in wildlife, it is rare to have someone with extensive experience with bats. And with experts estimating that 52% of bat species in North America are at risk of severe population declines in the next 15 years, time is important.

“It’s always great when you get together with an open mind and share techniques and knowledge,” said DNR biologist and 2025 Bat Blitz attendee John DePue, who specializes in bats. “While all our biologists are experienced with wildlife, some are just starting in the bat world and don’t have a lot of hands-on experience. Those of us who do are happy to teach. We’re passionate about bats, and we enjoy sharing our tools and techniques with others.”

Joining DePue at the Blitz was Kyle Seppanen, a wildlife researcher with the KBIC’s Natural Resource Department, who helped host the event.

Biologist looks for evidence of white-nose syndrome on wing of little brown bat

“It takes a lot of knowledge and skill to handle a bat safely without injuring it,” Seppanen said. “You need repetition to become proficient, so having experienced handlers on-site helps keep both people and bats safe.”

Three bat species were captured during the most recent Bat Blitz, including a little brown bat that was fitted with a small tracking transmitter before release.

These tiny radio transmitters are temporarily attached using a safe adhesive, allowing researchers to track the bats’ movements. Scientists use antennas like the Motus Wildlife Tracking System [ [link removed] ] to detect the signals for short periods of time, as the transmitters are designed to fall off after a few weeks. This data helps researchers better understand habitat threats and identify migration and roosting areas.

The data collected through the Blitz will also support field-based training for dog detection teams [ [link removed] ] and advance efforts to locate and protect bat roosts on lands managed by the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians in Emmet County.

A bat roost is any place a bat uses for shelter and protection from predators. Common roosting sites include caves, hollow trees and human-made structures such as attics or mines.

Bats often have multiple habitats for hibernation and breeding. Protecting maternity roosts is especially critical for the survival of Michigan’s bat populations, and knowing their location helps conservation efforts.

“Even though bats are sometimes referred to as ‘mice with wings,’ they are very different from mice,” said Jenny Wong of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, who also attended the Bat Blitz. “Rodents can produce dozens of litters a year, resulting in hundreds of offspring. Most of Michigan’s bat species give birth to just one pup annually. Even though some species can live 30 to 40 years, their low reproductive rate means every individual matters when it comes to rebuilding populations.”

researcher holds red bat in gloved hands

Anyone can help protect Michigan’s bats. Simple actions include reducing pesticide use, installing bat houses [ [link removed] ] and planting night-blooming flowers that attract moths, which serve as a food source for many bat species.

You can also assist the DNR and the Michigan Natural Features Inventory at Michigan State University by reporting bat roosts through the Roost Survey Form on the MNFI website [ [link removed] ].

“The public’s perspective on bats has changed,” Seppanen said. “People want to help bats now instead of immediately wanting to kill them because they understand how important bats are to our ecosystem and economy.”

Working with bats is not without risks, and handling them is not recommended due to the risk of rabies. Only about 1-5% of bats carry the disease, which is a significantly lower rate than raccoons, which test positive at roughly 20%.

To combat the risk of disease, the biologists involved with the Bat Blitz emphasize handling every bat with care during their collaborative training sessions.

“We wear personal protective equipment to protect ourselves while handling bats,” DePue said. “But we handle every bat like it’s the last of its kind on the planet.”

Another cross-agency Bat Blitz is scheduled for later this year.

“I’m hoping we can expand tribal participation and further strengthen these partnerships this year,” Wong said. “These efforts help us identify where surviving bat populations remain and focus conservation efforts where they are needed most.”

Learn more about Michigan’s bats and bat conservation at Michigan.gov/Bats [ [link removed] ].

Check out previous Showcasing the DNR stories in our archive at Michigan.gov/DNRStories [ [link removed] ]. To subscribe to upcoming Showcasing articles, sign up for free email delivery at Michigan.gov/DNREmail [ [link removed] ].

________________________________________________________________________

*Note to editors:* Contact: John Pepin <[email protected]>, Showcasing the DNR series editor, 906-226-1352. Accompanying photos and a text-only version of this story are available below for download. Caption information follows. Credit Michigan Department of Natural Resources, unless otherwise noted.

*Text-only version of this story [ [link removed] ]*.

*Cave [ [link removed] ]*: An abandoned mine shaft in Ontonagon County. Located at the base of the Keweenaw Peninsula, the mine serves as habitat for little brown bats.

*Cuddles [ [link removed] ]*: One of the reasons why white-nose syndrome is so deadly to bats is because of how social they are, as they participate in community grooming and hibernate close together. The disease can spread quickly because of this kind of close contact.

*Net [ [link removed] ]*: A red bat caught in a mist net, which researchers used to safely capture bats before carefully removing, examining and documenting them and then releasing them unharmed.

*Red bat [ [link removed] ]*: A researcher holds a red bat, one of Michigan’s nine bat species.

*Silver-haired bat [ [link removed] ]*: The silver-haired bat, shown here being held by a biologist, is one of four bat species that hibernate in caves and abandoned mine shafts throughout Michigan’s Keweenaw region. (photo courtesy of Keweenaw Bay Indian Community)

*Staff [ [link removed] ]*: Bat Blitz team members collect data from a captured little brown bat.

*Transmitter [ [link removed] ]*: Researchers fit a little brown bat with a small tracking transmitter, which will provide data to help them better understand habitat threats and identify bat migration and roosting areas. (photo courtesy of Keweenaw Bay Indian Community)

*Wing [ [link removed] ]*: A biologist looks for evidence of white-nose syndrome on the wing of a little brown bat. Little brown bats have a wingspan of 8 to 11 inches.

The Michigan Department of Natural Resources is committed to the conservation, protection, management, use and enjoyment of the state's natural and cultural resources for current and future generations. For more information, go to Michigan.gov/DNR [ [link removed] ].

X icon circle [ [link removed] ]facebook icon circle [ [link removed] ]YouTube icon circle [ [link removed] ]instagram icon [ [link removed] ]pinterest icon circle [ [link removed] ]email icon circle [ [link removed] ]Bluesky icon [ [link removed] ]

If you wish to no longer receive emails from the DNR,

please update your preferences here:

Manage Preferences [ [link removed]? ] | Unsubscribe All [ [link removed] ] | Help [ [link removed] ]

Need further assistance?

Contact Us [ [link removed] ] | Provide Feedback <[email protected]>

Visit us on our website: Michigan.gov/DNR [ [link removed] ]

________________________________________________________________________

This email was sent to [email protected] using GovDelivery Communications Cloud on behalf of: Michigan Department of Natural Resources · Deborah A. Stabenow Building, 525 W. Allegan St., PO Box 30028 Lansing MI 48909 · 1-800-439-1420

Share or view as webpage [ [link removed] ] | Update preferences [ [link removed] ]

DNR banner [ [link removed] ]

"Showcasing the DNR"

Close-up of silver-haired bat held by gloved hands

*A collaborative effort to protect Michigan’s bats*

*By AILEEN KEMME*

*Communications coordinator, Marketing and Outreach Division*

*Michigan Department of Natural Resources*

Jutting out into Lake Superior is the Keweenaw Peninsula, home to Michigan’s Copper Country.

This is where the earliest known metalworking in North America originated, with objects crafted by Indigenous peoples from Keweenaw copper becoming so prized that they have been discovered in archaeological sites throughout North America.

European settlers also established mining operations in the same region and made Michigan into the world’s leading copper producer by the early 20th century.

opening of an abandoned mine shaft

While virtually all the mining operations in the area have shuttered since then, the mines are not empty. The Keweenaw region is home to seven of Michigan’s nine bat species [ [link removed] ], with many of the bats calling the abandoned mines home.

Three of the Keweenaw’s bat species migrate south for the winter, with some, like the hoary bat, traveling as far as Central America before returning to their spring and summertime breeding grounds in North America.

The remaining four species spend their winters hibernating deep within caves and abandoned mine shafts throughout the region. Approximately 90% of Michigan’s hibernating bats overwinter in the Upper Peninsula, with these hibernation sites — called hibernacula" "— housing anywhere from a few individuals to tens of thousands.

While their erratic flight patterns and nocturnal behavior cause some people to fear them, bats play a vital role in Michigan’s ecosystem and economy.

A single bat can consume thousands of insects in one night, including disease-carrying mosquitoes and crop-damaging pests.

By naturally controlling insect populations, bats reduce the need for pesticides, with some studies estimating they save U.S. farmers more than $3 billion per year.

But Michigan’s ecologically and economically important bat populations are facing serious challenges, including habitat loss and becoming infected with white-nose syndrome.

group of bats cuddled together in a cave

White-nose syndrome, a deadly fungal disease, has eliminated roughly 90% of the state’s bats. Primarily affecting them while hibernating, the disease causes infected bats to awaken prematurely and rapidly deplete their fat reserves before they ultimately starve to death.

Entire colonies can be lost within a few years because the fungus spreads from cave to cave and from bat to bat through social grooming and close contact.

In response to the rapid decline of Michigan’s bat population, the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community organized a collaborative research effort known as the Bat Blitz in 2024.

Made possible through federal funding from the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the goal of the Bat Blitz was simple: to build skills for bat conservation entities by training together and sharing expertise across state, federal and tribal agencies.

Over the course of three nights, biologists from the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community’s Natural Resource Department were joined by partners from the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians, the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi, the Michigan Department of Natural Resources and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Bat Blitz team members collect data from a captured little brown bat.

Together, the team used mist nets — fine mesh nets resembling volleyball nets — to safely capture bats as they flew low over creeks and along backcountry roads in search of prey.

The biologists closely monitored the nets throughout the night, and once captured, the bats were carefully removed, examined and documented before being released unharmed.

Because Michigan is home to over 500 vertebrate wildlife species, this type of cross-agency training is crucial.

While it is common for environmental agencies in Michigan to have someone on staff who specializes in wildlife, it is rare to have someone with extensive experience with bats. And with experts estimating that 52% of bat species in North America are at risk of severe population declines in the next 15 years, time is important.

“It’s always great when you get together with an open mind and share techniques and knowledge,” said DNR biologist and 2025 Bat Blitz attendee John DePue, who specializes in bats. “While all our biologists are experienced with wildlife, some are just starting in the bat world and don’t have a lot of hands-on experience. Those of us who do are happy to teach. We’re passionate about bats, and we enjoy sharing our tools and techniques with others.”

Joining DePue at the Blitz was Kyle Seppanen, a wildlife researcher with the KBIC’s Natural Resource Department, who helped host the event.

Biologist looks for evidence of white-nose syndrome on wing of little brown bat

“It takes a lot of knowledge and skill to handle a bat safely without injuring it,” Seppanen said. “You need repetition to become proficient, so having experienced handlers on-site helps keep both people and bats safe.”

Three bat species were captured during the most recent Bat Blitz, including a little brown bat that was fitted with a small tracking transmitter before release.

These tiny radio transmitters are temporarily attached using a safe adhesive, allowing researchers to track the bats’ movements. Scientists use antennas like the Motus Wildlife Tracking System [ [link removed] ] to detect the signals for short periods of time, as the transmitters are designed to fall off after a few weeks. This data helps researchers better understand habitat threats and identify migration and roosting areas.

The data collected through the Blitz will also support field-based training for dog detection teams [ [link removed] ] and advance efforts to locate and protect bat roosts on lands managed by the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians in Emmet County.

A bat roost is any place a bat uses for shelter and protection from predators. Common roosting sites include caves, hollow trees and human-made structures such as attics or mines.

Bats often have multiple habitats for hibernation and breeding. Protecting maternity roosts is especially critical for the survival of Michigan’s bat populations, and knowing their location helps conservation efforts.

“Even though bats are sometimes referred to as ‘mice with wings,’ they are very different from mice,” said Jenny Wong of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, who also attended the Bat Blitz. “Rodents can produce dozens of litters a year, resulting in hundreds of offspring. Most of Michigan’s bat species give birth to just one pup annually. Even though some species can live 30 to 40 years, their low reproductive rate means every individual matters when it comes to rebuilding populations.”

researcher holds red bat in gloved hands

Anyone can help protect Michigan’s bats. Simple actions include reducing pesticide use, installing bat houses [ [link removed] ] and planting night-blooming flowers that attract moths, which serve as a food source for many bat species.

You can also assist the DNR and the Michigan Natural Features Inventory at Michigan State University by reporting bat roosts through the Roost Survey Form on the MNFI website [ [link removed] ].

“The public’s perspective on bats has changed,” Seppanen said. “People want to help bats now instead of immediately wanting to kill them because they understand how important bats are to our ecosystem and economy.”

Working with bats is not without risks, and handling them is not recommended due to the risk of rabies. Only about 1-5% of bats carry the disease, which is a significantly lower rate than raccoons, which test positive at roughly 20%.

To combat the risk of disease, the biologists involved with the Bat Blitz emphasize handling every bat with care during their collaborative training sessions.

“We wear personal protective equipment to protect ourselves while handling bats,” DePue said. “But we handle every bat like it’s the last of its kind on the planet.”

Another cross-agency Bat Blitz is scheduled for later this year.

“I’m hoping we can expand tribal participation and further strengthen these partnerships this year,” Wong said. “These efforts help us identify where surviving bat populations remain and focus conservation efforts where they are needed most.”

Learn more about Michigan’s bats and bat conservation at Michigan.gov/Bats [ [link removed] ].

Check out previous Showcasing the DNR stories in our archive at Michigan.gov/DNRStories [ [link removed] ]. To subscribe to upcoming Showcasing articles, sign up for free email delivery at Michigan.gov/DNREmail [ [link removed] ].

________________________________________________________________________

*Note to editors:* Contact: John Pepin <[email protected]>, Showcasing the DNR series editor, 906-226-1352. Accompanying photos and a text-only version of this story are available below for download. Caption information follows. Credit Michigan Department of Natural Resources, unless otherwise noted.

*Text-only version of this story [ [link removed] ]*.

*Cave [ [link removed] ]*: An abandoned mine shaft in Ontonagon County. Located at the base of the Keweenaw Peninsula, the mine serves as habitat for little brown bats.

*Cuddles [ [link removed] ]*: One of the reasons why white-nose syndrome is so deadly to bats is because of how social they are, as they participate in community grooming and hibernate close together. The disease can spread quickly because of this kind of close contact.

*Net [ [link removed] ]*: A red bat caught in a mist net, which researchers used to safely capture bats before carefully removing, examining and documenting them and then releasing them unharmed.

*Red bat [ [link removed] ]*: A researcher holds a red bat, one of Michigan’s nine bat species.

*Silver-haired bat [ [link removed] ]*: The silver-haired bat, shown here being held by a biologist, is one of four bat species that hibernate in caves and abandoned mine shafts throughout Michigan’s Keweenaw region. (photo courtesy of Keweenaw Bay Indian Community)

*Staff [ [link removed] ]*: Bat Blitz team members collect data from a captured little brown bat.

*Transmitter [ [link removed] ]*: Researchers fit a little brown bat with a small tracking transmitter, which will provide data to help them better understand habitat threats and identify bat migration and roosting areas. (photo courtesy of Keweenaw Bay Indian Community)

*Wing [ [link removed] ]*: A biologist looks for evidence of white-nose syndrome on the wing of a little brown bat. Little brown bats have a wingspan of 8 to 11 inches.

The Michigan Department of Natural Resources is committed to the conservation, protection, management, use and enjoyment of the state's natural and cultural resources for current and future generations. For more information, go to Michigan.gov/DNR [ [link removed] ].

X icon circle [ [link removed] ]facebook icon circle [ [link removed] ]YouTube icon circle [ [link removed] ]instagram icon [ [link removed] ]pinterest icon circle [ [link removed] ]email icon circle [ [link removed] ]Bluesky icon [ [link removed] ]

If you wish to no longer receive emails from the DNR,

please update your preferences here:

Manage Preferences [ [link removed]? ] | Unsubscribe All [ [link removed] ] | Help [ [link removed] ]

Need further assistance?

Contact Us [ [link removed] ] | Provide Feedback <[email protected]>

Visit us on our website: Michigan.gov/DNR [ [link removed] ]

________________________________________________________________________

This email was sent to [email protected] using GovDelivery Communications Cloud on behalf of: Michigan Department of Natural Resources · Deborah A. Stabenow Building, 525 W. Allegan St., PO Box 30028 Lansing MI 48909 · 1-800-439-1420

Message Analysis

- Sender: State of Michigan

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: MIchigan

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- govDelivery