| From | Anthropocene Alliance (A2) <[email protected]> |

| Subject | A2 Times: The lifeblood of the culture |

| Date | January 14, 2026 2:00 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

[[link removed]]

Amplifying frontline voices from A2 member groups.

‘The lifeblood of the culture’: the southern organizations protecting wetlands, oyster reefs, and their coastal heritage

In Bayou Bienvenue, they say that bald cypress trees used to grow so thick you didn’t need a paddle; some older Louisianans remember a time when you could just pull your boat along by the trees. The freshwater ecosystem was home to crawfish, alligators, and otters.

But the New Orleans bayou, which has a rich history – once home to maroon communities, formerly enslaved people who lived in the wetlands in the 19th century – has suffered decades of degradation. “People who lived on the bayou have been witnessing its loss in a single lifetime,” says Christina Lehew, the executive director of Common Ground Relief (an A2 member), noting that much of this loss is due to a century of canal dredging.

Coastal Louisiana is disappearing at a staggering pace. The state is losing a football field of coastal land every 100 minutes. Over the last century, a landmass the size of the state of Delaware has slipped into the open water. In addition to providing wildlife habitats, including for migratory birds, the wetlands act as powerful carbon sinks and help mitigate flooding in a region that bears the brunt of extreme weather.

A beaver dives beneath the surface. Photo Credit: Alexis Broz [[link removed]]

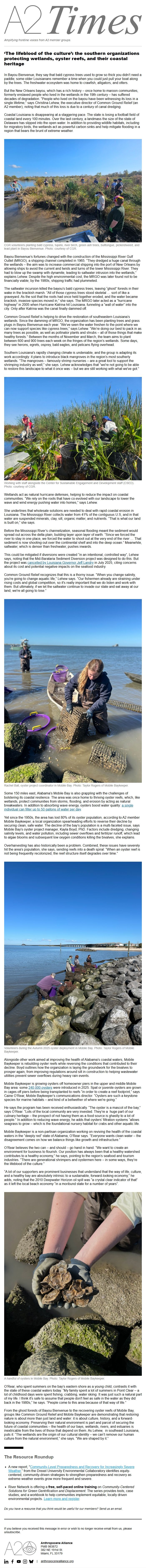

CGR volunteers planting bald cypress, tupelo, river birch, green ash trees, bulltongue, pickerelweed, and lead plant in Bayou Bienvenue. Photo: courtesy of CGR.

Bayou Bienvenue’s fortunes changed with the construction of the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet (MRGO), a shipping channel completed in 1965. “They dredged a huge canal through the wetlands – the aim was to increase commercial shipping into the port of New Orleans by allowing ships to avoid the current and twists and turns of the lower Mississippi River. They had to blow up the swamp with dynamite, leading to saltwater intrusion into the wetlands,” explains Lehew. Despite the high environmental cost, the MRGO was later found not to be financially viable; by the 1980s, shipping traffic had plummeted.

The saltwater incursion killed the bayou’s bald cypress trees, leaving “ghost” forests in their wake in the brackish marsh. “All of those cypress trees stood skeletal … sort of like a graveyard. As the soil that the roots had once held together eroded, and the water became brackish, invasive species moved in,” she says. The MRGO later acted as a “hurricane highway” in 2005 when Hurricane Katrina hit Louisiana, funneling a “wall of water” into the city. Only after Katrina was the canal finally dammed off.

Common Ground Relief is helping to drive the restoration of southeastern Louisiana’s wetlands. Since the damming of MRGO, the organization has been planting trees and grass plugs in Bayou Bienvenue each year. “We’ve seen the water freshen to the point where we can now support species like cypress trees,” says Lehew. “We’re doing our best to pack in as many trees as possible, as well as pollinator plants and shrubs – all of those things that make healthy forests.” Between the months of November and March, the team aims to plant between 600 and 900 trees each week on the fringes of the region’s wetlands. Some days, they see herons, egrets, osprey, bald eagles, and pelicans flying overhead.

Southern Louisiana's rapidly changing climate is undeniable, and the group is adapting its work accordingly: it plans to introduce black mangroves in the region’s most southerly wetlands. “The mangroves – famously shrimp nurseries – are a great tool to support the shrimping industry as well,” she says. Lehew acknowledges that “we're not going to be able to restore this landscape to what it once was – but we are still working with what we've got.”

A beaver dives beneath the surface. Photo Credit: Alexis Broz [[link removed]]

Working with staff alongside the Center for Sustainable Engagement and Development staff (CSED). Photo: courtesy of CGR.

Wetlands act as natural hurricane defenses, helping to reduce the impact on coastal communities. “We rely on the roots that have co-evolved with our landscape to lower the wave and wind energy pushing water into homes,” says Lehew.

She underlines that wholesale solutions are needed to deal with rapid coastal erosion in Louisiana. The Mississippi River collects water from 41% of the contiguous U.S, and in that water are suspended minerals, clay, silt, organic matter, and nutrients. “That is what our land is built on,” she says.

Before the Mississippi River’s channelization, seasonal flooding meant the sediment would spread out across the delta plain, building layer upon layer of earth. “Since we forced the river to stay in one place, we forced the water to shoot out at the very end of the river … That sediment is now shooting out over the continental shelf and into the deep ocean.” Meanwhile, saltwater, which is denser than freshwater, pushes inwards.

This could be mitigated if diversions were created “in an intentional, controlled way”, Lehew says, noting that the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion project was designed to do this. But the project was cancelled by Louisiana Governor Jeff Landry [[link removed]] in July 2025, citing concerns about its cost and potential negative impacts on the seafood industry.

Common Ground Relief recognizes that this is a thorny issue. “When you change salinity, you're going to change aquatic life,” Lehew says. “Our fishermen already are straining under rising costs and global competition, so it's really important that we do listen and work with them. But ultimately, if we let the saltwater continue to invade our state and eat away at our land, we're all going to lose.”

A beaver dives beneath the surface. Photo Credit: Alexis Broz [[link removed]]

Rachel Ball, oyster project coordinator in Mobile Bay. Photo: Taylor Rogers of Mobile Baykeeper.

Some 150 miles east, Alabama’s Mobile Bay is also grappling with the challenges of bolstering its coastal resilience. The area was once home to thriving oyster reefs, which, like wetlands, protect communities from storms, flooding, and erosion by acting as natural breakwaters. In addition to absorbing wave energy, oysters boost water quality: a single individual can filter up to 50 gallons of water per day [[link removed]] .

Yet since the 1950s, the area has lost 80% of its oyster population, according to A2 member Mobile Baykeeper, a local organization spearheading efforts to reverse their decline by securing clean, safe water. The decline of the bay’s population is a multi-faceted issue, says Mobile Bay’s oyster project manager, Kayla Boyd, PhD. Factors include dredging, changing salinity levels, and water pollution, including sewer overflows and fertilizer runoff, which lead to algae blooms and subsequent low oxygen conditions killing the bivalves, she explains.

Overharvesting has also historically been a problem. Combined, these issues have severely hit the area’s population, she says, sending reefs into a death spiral: “When an oyster reef is not being frequently recolonized, the reef structure itself degrades over time.”

A beaver dives beneath the surface. Photo Credit: Alexis Broz [[link removed]]

Volunteers during the Autumn 2025 oyster deployment in Mobile Bay. Photo: Taylor Rogers of Mobile Baykeeper.

Alongside other work aimed at improving the health of Alabama’s coastal waters, Mobile Baykeeper is rebuilding oyster reefs while reversing the conditions that contributed to their decline. Boyd outlines how the organization is laying the groundwork for the bivalves to prosper again, from improving regulations around silt in construction to helping wastewater utilities prevent sewer overflows during heavy rain events.

Mobile Baykeeper is growing oysters off homeowner piers in the upper and middle Mobile Bay area: some 240,000 oysters [[link removed]] were introduced in 2025. Spat or juvenile oysters are grown in cages off piers before being transplanted to reefs “in order to create a reef footprint,” says Caine O’Rear, Mobile Baykeeper’s communications director. “Oysters are such a keystone species for marine habitats – and kind of a bellwether of where we're going.”

He says the program has been received enthusiastically. “The oyster is a mascot of the bay,” says O’Rear. “Lots of the local community are very invested. They’re a huge part of our culinary heritage – the prospect of not having them as a food source is ghastly to a lot of people.” In addition to reducing wave energy, he adds that oysters’ filtration systems “allows seagrass to grow – which is the foundational nursery habitat for crabs and other aquatic life.

Mobile Baykeeper is a non-partisan organization working on reviving the health of the coastal waters in the “deeply red” state of Alabama, O’Rear says. “Everyone wants clean water – the disagreement comes on how we balance things like growth and infrastructure.”

O’Rear believes the two can – and should – go hand in hand. “We want to create an environment for business to flourish. Our position has always been that a healthy watershed contributes to a healthy economy,” he says, pointing to the region’s seafood and tourism industries. “There are generational shrimpers and oystermen here – in some ways, they’re the lifeblood of the culture.”

“A lot of our supporters are prominent businesses that understand that the way of life, culture, and a healthy bay are absolutely intrinsic to a sustainable, forward-looking economy,” he adds, noting that the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill was “a crystal clear indicator of that” as it left the local beach economy “in a moribund state for a number of years”.

A beaver dives beneath the surface. Photo Credit: Alexis Broz [[link removed]]

A handful of oysters in Mobile Bay. Photo: Taylor Rogers of Mobile Baykeeper.

O’Rear, who spent summers on the bay’s eastern shore as a young child, contrasts it with the state of these coastal waters today. “My family spent a lot of summers in Point Clear – a lot of childhood days were spent fishing, crabbing, water skiing. It was just such a natural part of my life. I think it's safe to assume that people don't feel as safe in the water as they did back in the 1980s,” he says. “People come to this area because of that way of life.”

From the ghost forests of Bayou Bienvenue to the recovering oyster reefs of Mobile Bay, groups like Common Ground Relief and Mobile Baykeeper are demonstrating that restoring nature is about more than just land and water: it is about culture, history, and a forward-looking economy. Preserving their natural environment is part and parcel of securing the future of coastal communities – the health of our bays, wetlands, rivers, and estuaries is inextricable from the lives of those that depend on them. As Lehew, in southeast Louisiana, puts it: “The wetlands are the origin of our cultural identity – we can’t remove our human culture from the natural environment,” she says. “We are shaped by it.”

The Resource Roundup

* A new report, " Community-Level Preparedness and Recovery for Increasingly Severe Weather [[link removed]] ,” from the Drexel University Environmental Collaboratory identifies equity-centered, community-driven strategies to strengthen preparedness and recovery as extreme weather events grow more frequent and severe.

* River Network is offering a free, self-paced online training on Community-Centered Solutions for Green Gentrification and Displacement . The series provides tools, case studies, and a workbook to help communities implement equitable, locally driven environmental projects. Learn more and register [[link removed]] .

Do you have a resource that you think would be useful for our members? Send us an email.

If you believe you received this message in error or wish to no longer receive email from us, please unsubscribe: [link removed] .

[[link removed]] Anthropocene Alliance

PMB 983872

382 NE 191st St.

Miami, FL 33179

[link removed] [[link removed]] [link removed] [[link removed]] [link removed] [[link removed]] [link removed] [[link removed]] [link removed] [[link removed]] | anthropocenealliance.org [[link removed]]

Amplifying frontline voices from A2 member groups.

‘The lifeblood of the culture’: the southern organizations protecting wetlands, oyster reefs, and their coastal heritage

In Bayou Bienvenue, they say that bald cypress trees used to grow so thick you didn’t need a paddle; some older Louisianans remember a time when you could just pull your boat along by the trees. The freshwater ecosystem was home to crawfish, alligators, and otters.

But the New Orleans bayou, which has a rich history – once home to maroon communities, formerly enslaved people who lived in the wetlands in the 19th century – has suffered decades of degradation. “People who lived on the bayou have been witnessing its loss in a single lifetime,” says Christina Lehew, the executive director of Common Ground Relief (an A2 member), noting that much of this loss is due to a century of canal dredging.

Coastal Louisiana is disappearing at a staggering pace. The state is losing a football field of coastal land every 100 minutes. Over the last century, a landmass the size of the state of Delaware has slipped into the open water. In addition to providing wildlife habitats, including for migratory birds, the wetlands act as powerful carbon sinks and help mitigate flooding in a region that bears the brunt of extreme weather.

A beaver dives beneath the surface. Photo Credit: Alexis Broz [[link removed]]

CGR volunteers planting bald cypress, tupelo, river birch, green ash trees, bulltongue, pickerelweed, and lead plant in Bayou Bienvenue. Photo: courtesy of CGR.

Bayou Bienvenue’s fortunes changed with the construction of the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet (MRGO), a shipping channel completed in 1965. “They dredged a huge canal through the wetlands – the aim was to increase commercial shipping into the port of New Orleans by allowing ships to avoid the current and twists and turns of the lower Mississippi River. They had to blow up the swamp with dynamite, leading to saltwater intrusion into the wetlands,” explains Lehew. Despite the high environmental cost, the MRGO was later found not to be financially viable; by the 1980s, shipping traffic had plummeted.

The saltwater incursion killed the bayou’s bald cypress trees, leaving “ghost” forests in their wake in the brackish marsh. “All of those cypress trees stood skeletal … sort of like a graveyard. As the soil that the roots had once held together eroded, and the water became brackish, invasive species moved in,” she says. The MRGO later acted as a “hurricane highway” in 2005 when Hurricane Katrina hit Louisiana, funneling a “wall of water” into the city. Only after Katrina was the canal finally dammed off.

Common Ground Relief is helping to drive the restoration of southeastern Louisiana’s wetlands. Since the damming of MRGO, the organization has been planting trees and grass plugs in Bayou Bienvenue each year. “We’ve seen the water freshen to the point where we can now support species like cypress trees,” says Lehew. “We’re doing our best to pack in as many trees as possible, as well as pollinator plants and shrubs – all of those things that make healthy forests.” Between the months of November and March, the team aims to plant between 600 and 900 trees each week on the fringes of the region’s wetlands. Some days, they see herons, egrets, osprey, bald eagles, and pelicans flying overhead.

Southern Louisiana's rapidly changing climate is undeniable, and the group is adapting its work accordingly: it plans to introduce black mangroves in the region’s most southerly wetlands. “The mangroves – famously shrimp nurseries – are a great tool to support the shrimping industry as well,” she says. Lehew acknowledges that “we're not going to be able to restore this landscape to what it once was – but we are still working with what we've got.”

A beaver dives beneath the surface. Photo Credit: Alexis Broz [[link removed]]

Working with staff alongside the Center for Sustainable Engagement and Development staff (CSED). Photo: courtesy of CGR.

Wetlands act as natural hurricane defenses, helping to reduce the impact on coastal communities. “We rely on the roots that have co-evolved with our landscape to lower the wave and wind energy pushing water into homes,” says Lehew.

She underlines that wholesale solutions are needed to deal with rapid coastal erosion in Louisiana. The Mississippi River collects water from 41% of the contiguous U.S, and in that water are suspended minerals, clay, silt, organic matter, and nutrients. “That is what our land is built on,” she says.

Before the Mississippi River’s channelization, seasonal flooding meant the sediment would spread out across the delta plain, building layer upon layer of earth. “Since we forced the river to stay in one place, we forced the water to shoot out at the very end of the river … That sediment is now shooting out over the continental shelf and into the deep ocean.” Meanwhile, saltwater, which is denser than freshwater, pushes inwards.

This could be mitigated if diversions were created “in an intentional, controlled way”, Lehew says, noting that the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion project was designed to do this. But the project was cancelled by Louisiana Governor Jeff Landry [[link removed]] in July 2025, citing concerns about its cost and potential negative impacts on the seafood industry.

Common Ground Relief recognizes that this is a thorny issue. “When you change salinity, you're going to change aquatic life,” Lehew says. “Our fishermen already are straining under rising costs and global competition, so it's really important that we do listen and work with them. But ultimately, if we let the saltwater continue to invade our state and eat away at our land, we're all going to lose.”

A beaver dives beneath the surface. Photo Credit: Alexis Broz [[link removed]]

Rachel Ball, oyster project coordinator in Mobile Bay. Photo: Taylor Rogers of Mobile Baykeeper.

Some 150 miles east, Alabama’s Mobile Bay is also grappling with the challenges of bolstering its coastal resilience. The area was once home to thriving oyster reefs, which, like wetlands, protect communities from storms, flooding, and erosion by acting as natural breakwaters. In addition to absorbing wave energy, oysters boost water quality: a single individual can filter up to 50 gallons of water per day [[link removed]] .

Yet since the 1950s, the area has lost 80% of its oyster population, according to A2 member Mobile Baykeeper, a local organization spearheading efforts to reverse their decline by securing clean, safe water. The decline of the bay’s population is a multi-faceted issue, says Mobile Bay’s oyster project manager, Kayla Boyd, PhD. Factors include dredging, changing salinity levels, and water pollution, including sewer overflows and fertilizer runoff, which lead to algae blooms and subsequent low oxygen conditions killing the bivalves, she explains.

Overharvesting has also historically been a problem. Combined, these issues have severely hit the area’s population, she says, sending reefs into a death spiral: “When an oyster reef is not being frequently recolonized, the reef structure itself degrades over time.”

A beaver dives beneath the surface. Photo Credit: Alexis Broz [[link removed]]

Volunteers during the Autumn 2025 oyster deployment in Mobile Bay. Photo: Taylor Rogers of Mobile Baykeeper.

Alongside other work aimed at improving the health of Alabama’s coastal waters, Mobile Baykeeper is rebuilding oyster reefs while reversing the conditions that contributed to their decline. Boyd outlines how the organization is laying the groundwork for the bivalves to prosper again, from improving regulations around silt in construction to helping wastewater utilities prevent sewer overflows during heavy rain events.

Mobile Baykeeper is growing oysters off homeowner piers in the upper and middle Mobile Bay area: some 240,000 oysters [[link removed]] were introduced in 2025. Spat or juvenile oysters are grown in cages off piers before being transplanted to reefs “in order to create a reef footprint,” says Caine O’Rear, Mobile Baykeeper’s communications director. “Oysters are such a keystone species for marine habitats – and kind of a bellwether of where we're going.”

He says the program has been received enthusiastically. “The oyster is a mascot of the bay,” says O’Rear. “Lots of the local community are very invested. They’re a huge part of our culinary heritage – the prospect of not having them as a food source is ghastly to a lot of people.” In addition to reducing wave energy, he adds that oysters’ filtration systems “allows seagrass to grow – which is the foundational nursery habitat for crabs and other aquatic life.

Mobile Baykeeper is a non-partisan organization working on reviving the health of the coastal waters in the “deeply red” state of Alabama, O’Rear says. “Everyone wants clean water – the disagreement comes on how we balance things like growth and infrastructure.”

O’Rear believes the two can – and should – go hand in hand. “We want to create an environment for business to flourish. Our position has always been that a healthy watershed contributes to a healthy economy,” he says, pointing to the region’s seafood and tourism industries. “There are generational shrimpers and oystermen here – in some ways, they’re the lifeblood of the culture.”

“A lot of our supporters are prominent businesses that understand that the way of life, culture, and a healthy bay are absolutely intrinsic to a sustainable, forward-looking economy,” he adds, noting that the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill was “a crystal clear indicator of that” as it left the local beach economy “in a moribund state for a number of years”.

A beaver dives beneath the surface. Photo Credit: Alexis Broz [[link removed]]

A handful of oysters in Mobile Bay. Photo: Taylor Rogers of Mobile Baykeeper.

O’Rear, who spent summers on the bay’s eastern shore as a young child, contrasts it with the state of these coastal waters today. “My family spent a lot of summers in Point Clear – a lot of childhood days were spent fishing, crabbing, water skiing. It was just such a natural part of my life. I think it's safe to assume that people don't feel as safe in the water as they did back in the 1980s,” he says. “People come to this area because of that way of life.”

From the ghost forests of Bayou Bienvenue to the recovering oyster reefs of Mobile Bay, groups like Common Ground Relief and Mobile Baykeeper are demonstrating that restoring nature is about more than just land and water: it is about culture, history, and a forward-looking economy. Preserving their natural environment is part and parcel of securing the future of coastal communities – the health of our bays, wetlands, rivers, and estuaries is inextricable from the lives of those that depend on them. As Lehew, in southeast Louisiana, puts it: “The wetlands are the origin of our cultural identity – we can’t remove our human culture from the natural environment,” she says. “We are shaped by it.”

The Resource Roundup

* A new report, " Community-Level Preparedness and Recovery for Increasingly Severe Weather [[link removed]] ,” from the Drexel University Environmental Collaboratory identifies equity-centered, community-driven strategies to strengthen preparedness and recovery as extreme weather events grow more frequent and severe.

* River Network is offering a free, self-paced online training on Community-Centered Solutions for Green Gentrification and Displacement . The series provides tools, case studies, and a workbook to help communities implement equitable, locally driven environmental projects. Learn more and register [[link removed]] .

Do you have a resource that you think would be useful for our members? Send us an email.

If you believe you received this message in error or wish to no longer receive email from us, please unsubscribe: [link removed] .

[[link removed]] Anthropocene Alliance

PMB 983872

382 NE 191st St.

Miami, FL 33179

[link removed] [[link removed]] [link removed] [[link removed]] [link removed] [[link removed]] [link removed] [[link removed]] [link removed] [[link removed]] | anthropocenealliance.org [[link removed]]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Anthropocene Alliance

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- EveryAction