Email

NEW NATIONAL DATA: How many jail stays are due to missed court dates?

| From | Prison Policy Initiative <[email protected]> |

| Subject | NEW NATIONAL DATA: How many jail stays are due to missed court dates? |

| Date | January 8, 2026 3:42 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

52,000 people are behind bars every day simply for missing a court date.

Prison Policy Initiative updates for January 8, 2026 Exposing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

How many jail stays are due to missed court dates? [[link removed]] Failing to make it to a court appearance – routine for attorneys and witnesses – leads to 19 million additional nights in jail each year for people accused of crimes. [[link removed]]

by Jacob Kang-Brown

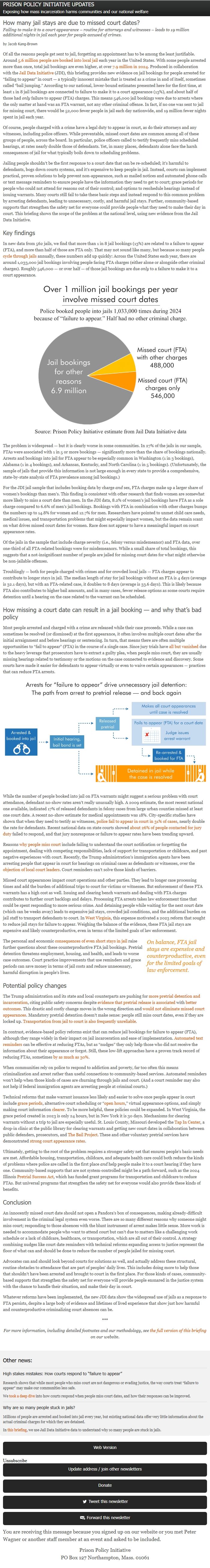

Of all the reasons people get sent to jail, forgetting an appointment has to be among the least justifiable. Around 5.6 million people are booked into local jail [[link removed]] each year in the United States. With some people arrested more than once, total jail bookings are even higher, at over 7.9 million in 2024 [[link removed]]. Produced in collaboration with the Jail Data Initiative [[link removed]] (JDI), this briefing provides new evidence on jail bookings for people arrested for “failing to appear” in court — a typically innocent mistake that is treated as a crime in and of itself, sometimes called “bail jumping.” According to our national, lower-bound estimates presented here for the first time, at least 1 in 8 jail bookings are connected to failure to make it to a court appearance (13%), and about half of those had only failure to appear (FTA) charges. This means 546,000 jail bookings were due to arrests where the only matter at hand was an FTA warrant, not any other criminal offense. In fact, if no one was sent to jail for missing court, there would be 52,000 fewer people in jail each day nationwide, and 19 million fewer nights spent in jail each year.

Of course, people charged with a crime have a legal duty to appear in court, as do their attorneys and any witnesses, including police officers. While preventable, missed court dates are common among all of these groups of people, across the board. In particular, police officers called to testify frequently miss scheduled hearings, at rates nearly double those of defendants. Yet, in many places, defendants alone face the harsh consequences of jail for what typically boils down to scheduling problems.

Jailing people shouldn’t be the first response to a court date that can be re-scheduled; it’s harmful to defendants, bogs down courts systems, and it’s expensive to keep people in jail. Instead, courts can implement practical, proven solutions to help prevent non-appearance, such as mailed notices and automated phone calls or text message reminders to ensure people have the information they need to get to court; grace periods for people who could not attend for reasons out of their control; and options to reschedule hearings instead of issuing warrants. Many courts still fail to take these basic steps and instead respond to this common problem by arresting defendants, leading to unnecessary, costly, and harmful jail stays. Further, community-based supports that strengthen the safety net for everyone could provide people what they need to make their day in court. This briefing shows the scope of the problem at the national level, using new evidence from the Jail Data Initiative.

Key findings

In new data from 562 jails, we find that more than 1 in 8 jail bookings (13%) are related to a failure to appear (FTA), and more than half of those are FTA only. That may not sound like many, but because so many people cycle through jails [[link removed]] annually, these numbers add up quickly: Across the United States each year, there are around 1,033,000 jail bookings involving people facing FTA charges (either alone or alongside other criminal charges). Roughly 546,000 — or over half — of those jail bookings are due only to a failure to make it to a court appearance.

The problem is widespread — but it is clearly worse in some communities. In 27% of the jails in our sample, FTAs were associated with 1 in 5 or more bookings — significantly more than the share of bookings nationally. Arrests and bookings into jail for FTA appear to be especially common in Washington (1 in 3 bookings), Alabama (1 in 4 bookings), and Arkansas, Kentucky, and North Carolina (1 in 5 bookings). (Unfortunately, the sample of jails that provide this information is not large enough in every state to provide a comprehensive, state-by-state analysis of FTA prevalence among jail bookings.)

For the JDI jail sample that includes booking data by charge and sex, FTA charges make up a larger share of women’s bookings than men’s. This finding is consistent with other research that finds women are somewhat more likely to miss a court date than men. In the JDI data, 8.2% of women’s jail bookings have FTA as a sole charge compared to 6.6% of men’s jail bookings. Bookings with FTA in combination with other charges bumps the numbers up to 14.8% for women and 12.7% for men. Researchers have pointed to unmet child care needs, medical issues, and transportation problems that might especially impact women, but the data remain scant on what drives missed court dates for women. Race does not appear to have a meaningful impact on court appearance rates.

Of the jails in the sample that include charge severity (i.e., felony versus misdemeanor) and FTA data, over one-third of all FTA-related bookings were for misdemeanors. While a small share of total bookings, this suggests that a not-insignificant number of people are jailed for missing court dates for what might otherwise be non-jailable offenses.

Troublingly — both for people charged with crimes and for crowded local jails — FTA charges appear to contribute to longer stays in jail. The median length of stay for jail bookings without an FTA is 4 days (average is 32.1 days), but with an FTA-related case, it doubles to 8 days (average is 33.6 days). This is likely because FTA also contributes to higher bail amounts, and in many cases, fewer release options as some courts require detention until a hearing on the case related to the warrant can be scheduled.

How missing a court date can result in a jail booking — and why that’s bad policy

Most people arrested and charged with a crime are released while their case proceeds. While a case can sometimes be resolved (or dismissed) at the first appearance, it often involves multiple court dates after the initial arraignment and before hearings or sentencing. In turn, that means there are often multiple opportunities to “fail to appear” (FTA) in the course of a single case. Since jury trials have all but vanished [[link removed]]due to the heavy leverage that prosecutors have to extract a guilty plea, when people miss court, they are usually missing hearings related to testimony or the motions on the case connected to evidence and discovery. Some courts have made it easier for defendants to appear virtually or even to waive certain appearances — practices that can reduce FTA arrests.

While the number of people booked into jail on FTA warrants might suggest a serious problem with court attendance, defendant no-show rates aren’t really unusually high. A 2009 estimate, the most recent national one available, indicated 17% of released defendants in felony cases from large urban counties missed at least one court date. A recent no-show estimate for medical appointments was 18%. City-specific studies have shown that when they need to testify as witnesses, police fail to appear in court in 31% of cases [[link removed]], nearly double the rate for defendants. Recent national data on state courts showed about 26% of people contacted for jury duty [[link removed]] failed to respond, and that jury nonresponse or failure to appear rates have been trending upward.

Reasons why people miss court [[link removed]] include failing to understand the court notification or forgetting the appointment, dealing with competing responsibilities, lack of support for transportation or childcare, and past negative experiences with court. Recently, the Trump administration’s immigration agents have been arresting people that appear in court for hearings on criminal cases as defendants or witnesses, over the objection of local court leaders [[link removed]]. Court reminders can’t solve those kinds of barriers.

Missed court appearances impact court operations and other parties. They lead to longer case processing times and add the burden of additional trips to court for victims or witnesses. But enforcement of these FTA warrants has a high cost as well. Issuing and clearing bench warrants and dealing with FTA charges contributes to further court backlogs and delays. Processing FTA arrests takes law enforcement time that could be spent responding to more serious crime. And detaining people while waiting for the next court date (which can be weeks away) leads to expensive jail stays, crowded jail conditions, and the additional burden on jail staff to transport defendants to court. In West Virginia [[link removed]], this expense motivated a 2023 reform that sought to reduce jail stays for failure to appear. Weighing the balance of the evidence, these FTA jail stays are expensive and likely counterproductive, even in terms of the limited goals of law enforcement.

On balance, FTA jail stays are expensive and counterproductive, even for the limited goals of law enforcement. The personal and economic consequences of even short stays in jail [[link removed]] raise further questions about these counterproductive FTA jail bookings. Pretrial detention threatens employment, housing, and health, and leads to worse case outcomes. Court practice improvements that use reminders and grace periods can save money in terms of jail costs and reduce unnecessary, harmful disruption in people’s lives.

Potential policy changes

The Trump administration and its state and local counterparts are pushing for more pretrial detention and incarceration [[link removed]], citing public safety concerns despite evidence that pretrial release is associated [[link removed]] with better outcomes [[link removed]]. This drastic and costly change moves in the wrong direction and would not eliminate missed court appearances [[link removed]]. Mandatory pretrial detention doesn’t make sense: people still miss court dates, even if they are locked up. Transportation from jail to court is also frequently unreliable. [[link removed]]

In contrast, evidence-based policy reforms exist that can reduce jail bookings for failure to appear (FTA), although they range widely in their impact on jail incarceration and ease of implementation. Automated text reminders [[link removed]] can be effective at reducing FTAs, but as “nudges” they only help those who did not receive the information about their appearance or forgot. Still, these low-lift approaches have a proven track record of reducing FTAs, sometimes by as much as 30% [[link removed]].

When communities rely on police to respond to addiction and poverty, far too often this means criminalization and arrest rather than useful connections to community-based services. Automated reminders won’t help when those kinds of cases are churning through jails and court. (And a court reminder may also not help if federal immigration agents are arresting people at criminal courts.)

Technical reforms that make warrant issuance less likely and easier to solve once people appear in court include grace [[link removed]] periods [[link removed]], alternative court scheduling or “ open hours [[link removed]],” virtual appearance options, and simply making court information clearer [[link removed]]. To be more helpful, these policies could be expanded. In West Virginia, the grace period created in 2023 is only 24 hours, but in New York it is 30 days. Mechanisms for clearing warrants without a trip to jail are especially useful. St. Louis County, Missouri developed the Tap In Center [[link removed]], a drop-in clinic at the public library for clearing warrants and getting new court dates in collaboration between public defenders, prosecutors, and The Bail Project [[link removed]]. These and other voluntary pretrial services have demonstrated strong court appearance rates [[link removed]].

Ultimately, getting to the root of the problem requires a stronger safety net that ensures people’s basic needs are met. Affordable housing, transportation, childcare, and adequate health care could both reduce the kinds of problems where police are called in the first place and help people make it to a court hearing if they have one. Community-based supports that are not system-controlled might be a path forward, such as the 2024 Illinois Pretrial Success Act [[link removed]], which has funded grant programs for transportation and childcare to reduce FTAs. But universal programs that strengthen the safety net for everyone would also provide these kinds of benefits.

Conclusion

An innocently missed court date should not open a Pandora’s box of consequences, making already-difficult involvement in the criminal legal system even worse. There are so many different reasons why someone might miss court; responding to those absences with the blunt instrument of arrest makes little sense. More work is needed to accommodate people who want to attend court but can’t due to matters like a challenging work schedule or a lack of childcare, healthcare, or transportation, which are all out of their control. A strategy combining nudges like court date reminders with technical reforms expanding access to justice represent the floor of what can and should be done to reduce the number of people jailed for missing court.

Advocates can and should look beyond courts for solutions as well, and actually address these structural, routine obstacles to attendance that are part of peoples’ daily lives. This includes doing more to help those that shouldn’t have been arrested and brought to court in the first place. For those kinds of cases, community-based supports that strengthen the safety net for everyone will provide people ensnared in the justice system with the chance to handle their situation, and make their day in court.

Whatever reforms have been implemented, the new JDI data show the widespread use of jails as a response to FTA persists, despite a large body of evidence and lifetimes of lived experience that show just how harmful and counterproductive criminalizing court absences can be.

***

For more information, including detailed footnotes and our methodology, see the full version of this briefing [[link removed]] on our website.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: High stakes mistakes: How courts respond to “failure to appear” [[link removed]]

Research shows that while most people who miss court are not dangerous or evading justice, the way courts treat “failure to appear” may make our communities less safe.

We took a deep dive [[link removed]] into how courts respond when people miss court dates, and how their responses can be improved.

Why are so many people stuck in jails? [[link removed]]

Millions of people are arrested and booked into jail every year, but existing national data offer very little information about the actual criminal charges for which they are detained.

In this briefing [[link removed]], we use Jail Data Initiative data to understand why so many people are stuck in jails.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives [[link removed]])

Update your newsletter subscriptions [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Did someone forward this to you? If you enjoyed reading, please subscribe! [[link removed]] Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Prison Policy Initiative updates for January 8, 2026 Exposing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

How many jail stays are due to missed court dates? [[link removed]] Failing to make it to a court appearance – routine for attorneys and witnesses – leads to 19 million additional nights in jail each year for people accused of crimes. [[link removed]]

by Jacob Kang-Brown

Of all the reasons people get sent to jail, forgetting an appointment has to be among the least justifiable. Around 5.6 million people are booked into local jail [[link removed]] each year in the United States. With some people arrested more than once, total jail bookings are even higher, at over 7.9 million in 2024 [[link removed]]. Produced in collaboration with the Jail Data Initiative [[link removed]] (JDI), this briefing provides new evidence on jail bookings for people arrested for “failing to appear” in court — a typically innocent mistake that is treated as a crime in and of itself, sometimes called “bail jumping.” According to our national, lower-bound estimates presented here for the first time, at least 1 in 8 jail bookings are connected to failure to make it to a court appearance (13%), and about half of those had only failure to appear (FTA) charges. This means 546,000 jail bookings were due to arrests where the only matter at hand was an FTA warrant, not any other criminal offense. In fact, if no one was sent to jail for missing court, there would be 52,000 fewer people in jail each day nationwide, and 19 million fewer nights spent in jail each year.

Of course, people charged with a crime have a legal duty to appear in court, as do their attorneys and any witnesses, including police officers. While preventable, missed court dates are common among all of these groups of people, across the board. In particular, police officers called to testify frequently miss scheduled hearings, at rates nearly double those of defendants. Yet, in many places, defendants alone face the harsh consequences of jail for what typically boils down to scheduling problems.

Jailing people shouldn’t be the first response to a court date that can be re-scheduled; it’s harmful to defendants, bogs down courts systems, and it’s expensive to keep people in jail. Instead, courts can implement practical, proven solutions to help prevent non-appearance, such as mailed notices and automated phone calls or text message reminders to ensure people have the information they need to get to court; grace periods for people who could not attend for reasons out of their control; and options to reschedule hearings instead of issuing warrants. Many courts still fail to take these basic steps and instead respond to this common problem by arresting defendants, leading to unnecessary, costly, and harmful jail stays. Further, community-based supports that strengthen the safety net for everyone could provide people what they need to make their day in court. This briefing shows the scope of the problem at the national level, using new evidence from the Jail Data Initiative.

Key findings

In new data from 562 jails, we find that more than 1 in 8 jail bookings (13%) are related to a failure to appear (FTA), and more than half of those are FTA only. That may not sound like many, but because so many people cycle through jails [[link removed]] annually, these numbers add up quickly: Across the United States each year, there are around 1,033,000 jail bookings involving people facing FTA charges (either alone or alongside other criminal charges). Roughly 546,000 — or over half — of those jail bookings are due only to a failure to make it to a court appearance.

The problem is widespread — but it is clearly worse in some communities. In 27% of the jails in our sample, FTAs were associated with 1 in 5 or more bookings — significantly more than the share of bookings nationally. Arrests and bookings into jail for FTA appear to be especially common in Washington (1 in 3 bookings), Alabama (1 in 4 bookings), and Arkansas, Kentucky, and North Carolina (1 in 5 bookings). (Unfortunately, the sample of jails that provide this information is not large enough in every state to provide a comprehensive, state-by-state analysis of FTA prevalence among jail bookings.)

For the JDI jail sample that includes booking data by charge and sex, FTA charges make up a larger share of women’s bookings than men’s. This finding is consistent with other research that finds women are somewhat more likely to miss a court date than men. In the JDI data, 8.2% of women’s jail bookings have FTA as a sole charge compared to 6.6% of men’s jail bookings. Bookings with FTA in combination with other charges bumps the numbers up to 14.8% for women and 12.7% for men. Researchers have pointed to unmet child care needs, medical issues, and transportation problems that might especially impact women, but the data remain scant on what drives missed court dates for women. Race does not appear to have a meaningful impact on court appearance rates.

Of the jails in the sample that include charge severity (i.e., felony versus misdemeanor) and FTA data, over one-third of all FTA-related bookings were for misdemeanors. While a small share of total bookings, this suggests that a not-insignificant number of people are jailed for missing court dates for what might otherwise be non-jailable offenses.

Troublingly — both for people charged with crimes and for crowded local jails — FTA charges appear to contribute to longer stays in jail. The median length of stay for jail bookings without an FTA is 4 days (average is 32.1 days), but with an FTA-related case, it doubles to 8 days (average is 33.6 days). This is likely because FTA also contributes to higher bail amounts, and in many cases, fewer release options as some courts require detention until a hearing on the case related to the warrant can be scheduled.

How missing a court date can result in a jail booking — and why that’s bad policy

Most people arrested and charged with a crime are released while their case proceeds. While a case can sometimes be resolved (or dismissed) at the first appearance, it often involves multiple court dates after the initial arraignment and before hearings or sentencing. In turn, that means there are often multiple opportunities to “fail to appear” (FTA) in the course of a single case. Since jury trials have all but vanished [[link removed]]due to the heavy leverage that prosecutors have to extract a guilty plea, when people miss court, they are usually missing hearings related to testimony or the motions on the case connected to evidence and discovery. Some courts have made it easier for defendants to appear virtually or even to waive certain appearances — practices that can reduce FTA arrests.

While the number of people booked into jail on FTA warrants might suggest a serious problem with court attendance, defendant no-show rates aren’t really unusually high. A 2009 estimate, the most recent national one available, indicated 17% of released defendants in felony cases from large urban counties missed at least one court date. A recent no-show estimate for medical appointments was 18%. City-specific studies have shown that when they need to testify as witnesses, police fail to appear in court in 31% of cases [[link removed]], nearly double the rate for defendants. Recent national data on state courts showed about 26% of people contacted for jury duty [[link removed]] failed to respond, and that jury nonresponse or failure to appear rates have been trending upward.

Reasons why people miss court [[link removed]] include failing to understand the court notification or forgetting the appointment, dealing with competing responsibilities, lack of support for transportation or childcare, and past negative experiences with court. Recently, the Trump administration’s immigration agents have been arresting people that appear in court for hearings on criminal cases as defendants or witnesses, over the objection of local court leaders [[link removed]]. Court reminders can’t solve those kinds of barriers.

Missed court appearances impact court operations and other parties. They lead to longer case processing times and add the burden of additional trips to court for victims or witnesses. But enforcement of these FTA warrants has a high cost as well. Issuing and clearing bench warrants and dealing with FTA charges contributes to further court backlogs and delays. Processing FTA arrests takes law enforcement time that could be spent responding to more serious crime. And detaining people while waiting for the next court date (which can be weeks away) leads to expensive jail stays, crowded jail conditions, and the additional burden on jail staff to transport defendants to court. In West Virginia [[link removed]], this expense motivated a 2023 reform that sought to reduce jail stays for failure to appear. Weighing the balance of the evidence, these FTA jail stays are expensive and likely counterproductive, even in terms of the limited goals of law enforcement.

On balance, FTA jail stays are expensive and counterproductive, even for the limited goals of law enforcement. The personal and economic consequences of even short stays in jail [[link removed]] raise further questions about these counterproductive FTA jail bookings. Pretrial detention threatens employment, housing, and health, and leads to worse case outcomes. Court practice improvements that use reminders and grace periods can save money in terms of jail costs and reduce unnecessary, harmful disruption in people’s lives.

Potential policy changes

The Trump administration and its state and local counterparts are pushing for more pretrial detention and incarceration [[link removed]], citing public safety concerns despite evidence that pretrial release is associated [[link removed]] with better outcomes [[link removed]]. This drastic and costly change moves in the wrong direction and would not eliminate missed court appearances [[link removed]]. Mandatory pretrial detention doesn’t make sense: people still miss court dates, even if they are locked up. Transportation from jail to court is also frequently unreliable. [[link removed]]

In contrast, evidence-based policy reforms exist that can reduce jail bookings for failure to appear (FTA), although they range widely in their impact on jail incarceration and ease of implementation. Automated text reminders [[link removed]] can be effective at reducing FTAs, but as “nudges” they only help those who did not receive the information about their appearance or forgot. Still, these low-lift approaches have a proven track record of reducing FTAs, sometimes by as much as 30% [[link removed]].

When communities rely on police to respond to addiction and poverty, far too often this means criminalization and arrest rather than useful connections to community-based services. Automated reminders won’t help when those kinds of cases are churning through jails and court. (And a court reminder may also not help if federal immigration agents are arresting people at criminal courts.)

Technical reforms that make warrant issuance less likely and easier to solve once people appear in court include grace [[link removed]] periods [[link removed]], alternative court scheduling or “ open hours [[link removed]],” virtual appearance options, and simply making court information clearer [[link removed]]. To be more helpful, these policies could be expanded. In West Virginia, the grace period created in 2023 is only 24 hours, but in New York it is 30 days. Mechanisms for clearing warrants without a trip to jail are especially useful. St. Louis County, Missouri developed the Tap In Center [[link removed]], a drop-in clinic at the public library for clearing warrants and getting new court dates in collaboration between public defenders, prosecutors, and The Bail Project [[link removed]]. These and other voluntary pretrial services have demonstrated strong court appearance rates [[link removed]].

Ultimately, getting to the root of the problem requires a stronger safety net that ensures people’s basic needs are met. Affordable housing, transportation, childcare, and adequate health care could both reduce the kinds of problems where police are called in the first place and help people make it to a court hearing if they have one. Community-based supports that are not system-controlled might be a path forward, such as the 2024 Illinois Pretrial Success Act [[link removed]], which has funded grant programs for transportation and childcare to reduce FTAs. But universal programs that strengthen the safety net for everyone would also provide these kinds of benefits.

Conclusion

An innocently missed court date should not open a Pandora’s box of consequences, making already-difficult involvement in the criminal legal system even worse. There are so many different reasons why someone might miss court; responding to those absences with the blunt instrument of arrest makes little sense. More work is needed to accommodate people who want to attend court but can’t due to matters like a challenging work schedule or a lack of childcare, healthcare, or transportation, which are all out of their control. A strategy combining nudges like court date reminders with technical reforms expanding access to justice represent the floor of what can and should be done to reduce the number of people jailed for missing court.

Advocates can and should look beyond courts for solutions as well, and actually address these structural, routine obstacles to attendance that are part of peoples’ daily lives. This includes doing more to help those that shouldn’t have been arrested and brought to court in the first place. For those kinds of cases, community-based supports that strengthen the safety net for everyone will provide people ensnared in the justice system with the chance to handle their situation, and make their day in court.

Whatever reforms have been implemented, the new JDI data show the widespread use of jails as a response to FTA persists, despite a large body of evidence and lifetimes of lived experience that show just how harmful and counterproductive criminalizing court absences can be.

***

For more information, including detailed footnotes and our methodology, see the full version of this briefing [[link removed]] on our website.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Other news: High stakes mistakes: How courts respond to “failure to appear” [[link removed]]

Research shows that while most people who miss court are not dangerous or evading justice, the way courts treat “failure to appear” may make our communities less safe.

We took a deep dive [[link removed]] into how courts respond when people miss court dates, and how their responses can be improved.

Why are so many people stuck in jails? [[link removed]]

Millions of people are arrested and booked into jail every year, but existing national data offer very little information about the actual criminal charges for which they are detained.

In this briefing [[link removed]], we use Jail Data Initiative data to understand why so many people are stuck in jails.

Please support our work [[link removed]]

Our work is made possible by private donations. Can you help us keep going? We can accept tax-deductible gifts online [[link removed]] or via paper checks sent to PO Box 127 Northampton MA 01061. Thank you!

Our other newsletters Ending prison gerrymandering ( archives [[link removed]]) Criminal justice research library ( archives [[link removed]])

Update your newsletter subscriptions [link removed].

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website [[link removed]] or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative [[link removed]]

PO Box 127

Northampton, Mass. 01061

Web Version [link removed] Unsubscribe [link removed] Update address / join other newsletters [link removed] Donate [[link removed]] Tweet this newsletter [link removed] Forward this newsletter [link removed]

You are receiving this message because you signed up on our website or you met Peter Wagner or another staff member at an event and asked to be included.

Prison Policy Initiative

PO Box 127 Northampton, Mass. 01061

Did someone forward this to you? If you enjoyed reading, please subscribe! [[link removed]] Web Version [link removed] | Update address [link removed] | Unsubscribe [link removed] | Share via: Twitter [link removed] Facebook [[link removed] Email [link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Prison Policy Initiative

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- Campaign Monitor