|

By Anthony J Evans, Associate Professor of Economics at ESCP Business School

Thus far, debates about the term “neoliberalism” have not been particularly constructive. I believe this rests on two separate (but related) questions:

1. Is “neoliberalism” a useful concept for understanding our political and economic system?

2. Is that system desirable?

There is a lot of academic literature that is grounded in the concept and the vast majority is used to critique capitalism. Indeed, use of the term “neoliberal” overwhelmingly grew as a pejorative. With origins in David Harvey, and embodied by academics such as Quinn Slobodian as well as writers like George Monbiot, “neoliberalism” is presented as something both real and detrimental. But there is a danger of conflating these two issues. There is a risk that the term is propagated because it serves as an effective rhetorical strategy, rather than the best means to clarify arguments. And there is a suspicion that ideological pre-commitments dominate a search for intellectual clarity. For non-Marxists and pro-market classical liberals or libertarians, is the label relevant?

Over the last decade or so there has been a notable attempt to “reclaim” neoliberalism, pushed by think tanks and journalists. Strategically, it might make sense to jump on the bandwagon, because part of the battle of ideas is contributing to how terms are understood. Neoliberalism thus becomes a contested brand. You have your museum, we have our bright and optimistic Reddit thread.

But there has also been consideration to the term from academics.

The common attitude amongst pro-capitalist scholars is to dispute the validity of the concept and ignore most of the literature as being flawed and ill-intentioned. Phil Magness has publicly rejected the label, and Vincent Geloso has cautioned against adopting it, even for strategic purposes. Embodying the attitude of many libertarians, Robert Lawson and Phil Magness have recently published a book called “Neoliberal Abstracts” which gathers summaries of actual peer-reviewed academic articles to highlight the plethora of absurd and baffling work being done in its name. Their contribution is funny and well timed. It also gives the impression that critics of neoliberalism have little to gain from a constructive engagement. But this would be false.

Consider the following three books: “The Neoliberal Revolution in Eastern Europe” (written by myself and Paul Dragos Aligica), Mark Pennington’s “Robust Political Economy”, and “Neoliberal Social Justice” by Nick Cowen. All serious academics working in top research institutions. We are perhaps best labelled as “classical liberals” but give sufficient scope to political economy in our research objectives to justify a normative context and the validity to advocate as well as analyse alternative systems. And we have used “neoliberal” as a descriptive, neutral term. I define it as “a political and economic philosophy that emphasises the role of markets to solve social problems” but also recognise that this might be a work in progress. Ultimately, however, we all utilise the concept and can broadly be considered to be neoliberals.

In my own research, I have suggested that neoliberalism has passed through four distinct phases and have also articulated my specific criticisms of neoliberal policy. For example, I think that two clear outcomes of neoliberalism are (i) independent and technocratic central banks; and (ii) a rejuvenation in state capitalism. Consider Alan Greenspan and Deng Xiaoping to be two of the most influential neoliberals of the twentieth century. Where I differ from strict neoliberals is that I think free banking would be a superior system to a centrally planned monetary system, and China’s economic transformation does not constitute an attractive transition plan. Where I differ from the critics of neoliberalism, however, is to say that independent central banks are preferable to political control of the money supply, and that state capitalism is better than no capitalism. Indeed, the fact that I am pragmatic in my judgments, and recognise that context plays an important role in judging the desirability of policy action, reveals how comfortable I am with being considered part of the “neoliberal thought collective”.

My main claim is that critics of neoliberalism should not dismiss neoliberal expertise.

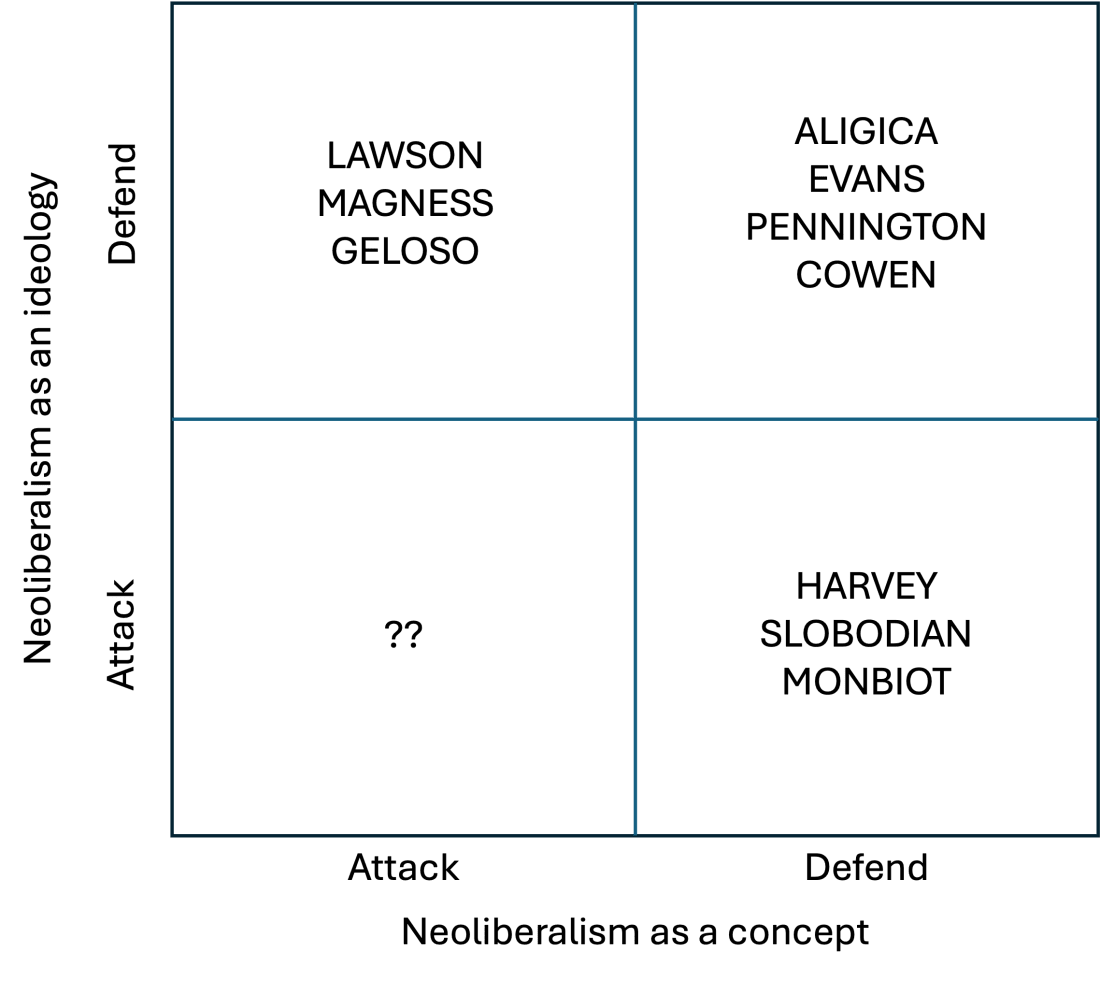

If we create a matrix displaying adherence to neoliberalism as a concept, but also as an ideology, we have four distinct categories. The polar opposites of Lawson, Magness, Geloso and Harvey, Slobodian, Monbiot (who are all, in their own ways, anti-neoliberal) should not detract from the potential for a constructive academic debate that attempts to take the concept seriously.

My most recent effort to pursue meaningful scholarly enquiry is a survey of recent critical histories of neoliberalism, just published by the journal ‘Critical Review’. In it, I pay particular attention to books by Philip Mirowski, Will Davies, Thomas Biebricher, Quinn Slobodian and Jessica Whyte. While disagreeing with large parts of their work, I have attempted a charitable reading and to treat them respectfully.

I hope that they will read my paper and provide an appropriate response. But I won’t hold my breath – previous reviews of work by Wendy Brown and George Monbiot have thus far gone unanswered. I guess as long as I don’t end up in the second edition of Neoliberal Abstracts, that will be a triumph of sorts!

Anthony J. Evans is Professor of Economics at ESCP Business School. He has been an Affiliate Faculty Member on the Microeconomics of Competitiveness Programme at Harvard Business School, and a Fulbright Scholar-in-Residence at San Jose State University.

His research areas are monetary economics and transitional economics. He works on topics related to competitiveness, central banking, and neoliberalism.

You’re currently a free subscriber to Insider. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription.

Paid subscribers support the IEA's charitable mission and receive special invites to exclusive events, including the thought-provoking IEA Book Club.

We are offering all new subscribers a special offer. For a limited time only, you will receive 15% off and a complimentary copy of Dr Stephen Davies’ latest book, Apocalypse Next: The Economics of Global Catastrophic Risks.