| From | xxxxxx <[email protected]> |

| Subject | Labor Solidarity Defends Against Deportations |

| Date | November 26, 2025 1:10 AM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

[[link removed]]

LABOR SOLIDARITY DEFENDS AGAINST DEPORTATIONS

[[link removed]]

In These Times Editors

November 24, 2025

In These Times

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

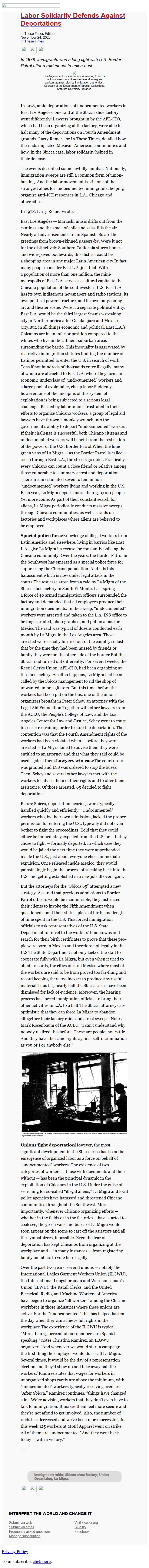

_ In 1978, immigrants won a long fight with U.S. Border Patrol after

a raid meant to union-bust. _

Los Angeles activists announce a meeting to recruit factory-based

committees to defend immigrant workers against raids by immigration

authorities., Courtesy of the Department of Special Collections,

Stanford University Libraries.

In 1978, amid deportations of undocumented workers in East Los

Angeles, one raid at the Sbicca shoe factory went differently: Lawyers

brought in by the AFL-CIO, which had been organizing at the factory,

were able to halt many of the deportations on Fourth Amendment

grounds. Larry Remer, for In These Times, detailed how the raids

impacted Mexican-American communities and how, in the Sbicca case,

labor solidarity helped in their defense.

The events described sound awfully familiar. Nationally, immigration

sweeps are still a common form of union-busting. And the labor

movement is still one of the strongest allies for undocumented

immigrants, helping organize anti-ICE responses in L.A., Chicago and

other cities.

In 1978, Larry Remer wrote:

East Los Angeles — Mariachi music drifts out from the cantinas

and the smell of chile and salsa fills the air. Nearly all

advertisements are in Spanish. So are the greetings from brown-skinned

passers-by. Were it not for the distinctively Southern California

stucco homes and wide-paved boulevards, this district could be

a shopping area in any major Latin American city.In fact, many people

consider East L.A. just that. With a population of more than one

million, the mini-metropolis of East L.A. serves as cultural capital

to the Chicano population of the southwestern U.S. East L.A. has its

own indigenous newspapers and radio stations, its own political power

structure, and its own burgeoning art and theater scene. Were it

a separate political entity, East L.A. would be the third largest

Spanish-speaking city in North America after Guadalajara and Mexico

City.But, in all things economic and political, East L.A.’s Chicanos

are in an inferior position compared to the whites who live in the

affluent suburban areas surrounding the barrio. This inequality is

aggravated by restrictive immigration statutes limiting the number of

Latinos permitted to enter the U.S. in search of work. Tens if not

hundreds of thousands enter illegally, many of whom are attracted to

East L.A. where they form an economic underclass of

“undocumented” workers and a large pool of exploitable, cheap

labor.Suddenly, however, one of the linchpins of this system of

exploitation is being subjected to a serious legal challenge. Backed

by labor unions frustrated in their efforts to organize Chicano

workers, a group of legal aid lawyers have thrown a monkey wrench

into the government’s ability to deport “undocumented”

workers. If their challenge is successful, both Chicano citizens and

undocumented workers will benefit from the restriction of the power of

the U.S. Border Patrol.When the lime green vans of La Migra — as

the Border Patrol is called — creep through East L.A., the

streets go quiet. Practically every Chicano can count a close friend

or relative among those vulnerable to summary arrest and deportation.

There are an estimated seven to ten million “undocumented”

workers living and working in the U.S. Each year, La Migra deports

more than 750,000 people. Yet more come. As part of their constant

search for aliens, La Migra periodically conducts massive sweeps

through Chicano communities, as well as raids on factories and

workplaces where aliens are believed to be employed.

SPECIAL POLICE FORCEKnowledge of illegal workers from Latin America

and elsewhere, living in barrios like East L.A., give La Migra its

excuse for constantly policing the Chicano community. Over the years,

the Border Patrol in the Southwest has emerged as a special police

force for suppressing the Chicano population. And it is this

harassment which is now under legal attack in the courts.The test case

arose from a raid by La Migra of the Sbicca shoe factory in South El

Monte. Last spring a force of 40 armed immigration officers

surrounded the factory and demanded that all employees produce their

immigration documents. In the sweep, “undocumented” workers

were arrested and taken to the L.A. INS office to be fingerprinted,

photographed, and put on a bus for Mexico.The raid was typical of

dozens conducted each month by La Migra in the Los Angeles area. Those

arrested were usually hurried out of the country so fast that by the

time they had been missed by friends or family they were on the other

side of the border.But the Sbicca raid turned out differently. For

several weeks, the Retail Clerks Union, AFL-CIO, had been organizing

at the shoe factory. As often happens, La Migra had been called by the

Sbicca management to rid the shop of unwanted union agitators. But

this time, before the workers had been put on the bus, one of the

union’s organizers brought in Peter Schey, an attorney with the

Legal Aid Foundation.Together with other lawyers from the ACLU, the

People’s College of Law, and the Los Angeles Center for Law and

Justice, Schey went to court to seek a restraining order to stop the

deportation. Their contention was that the Fourth Amendment rights of

the workers had been violated when — before they were

arrested — La Migra failed to advise them they were entitled to

an attorney and that what they said could be used against them.LAWYERS

WIN CASEThe court order was granted and INS was ordered to stop the

buses. Then, Schey and several other lawyers met with the workers to

advise them of their rights and to offer their assistance. Of those

arrested, 65 decided to fight deportation.

Before Sbicca, deportation hearings were typically handled quickly and

efficiently. “Undocumented” workers who, by their own

admission, lacked the proper permission for entering the U.S.,

typically did not even bother to fight the proceedings. Told that they

could either be immediately expelled from the U.S. or — if they

chose to fight — formally deported, in which case they would be

jailed the next time they were apprehended inside the U.S., just about

everyone chose immediate expulsion. Once released inside Mexico, they

would painstakingly begin the process of sneaking back into the U.S.

and getting established in a new job all over again.

But the attorneys for the “Sbicca 65” attempted a new

strategy. Assured that previous admissions to Border Patrol officers

would be inadmissible, they instructed their clients to invoke the

Fifth Amendment when questioned about their status, place of birth,

and length of time spent in the U.S. This forced immigration officials

to ask representatives of the U.S. State Department to travel to the

workers’ hometowns and search for their birth certificates to prove

that these peo- ple were born in Mexico and therefore not legally in

the U.S.The State Department not only lacked the staff to cooperate

fully with La Migra, but even when it tried to obtain records, the

cities of rural Mexico where most of the workers are said to be from

proved too far-flung and record keeping there too inexact to produce

any useful material.Thus far, nearly half the Sbicca cases have been

dismissed for lack of evidence. Moreover, the hearing process has

forced immigration officials to bring their other activities in L.A.

to a halt.The Sbicca attorneys are optimistic that they can force La

Migra to abandon altogether their factory raids and street sweeps.

Notes Mark Rosenbaum of the ACLU, “I can’t understand why

nobody realized this before. These are people, not cattle. And they

have the same rights against self-incrimination as you or I or

anybody else.”

UNIONS FIGHT DEPORTATIONHowever, the most significant development in

the Sbicca case has been the emergence of organized labor as a force

on behalf of “undocumented” workers. The existence of two

categories of workers — those with documents and those

without — has been the principal dynamic in the exploitation of

Chicanos in the U.S. Under the guise of searching for so-called

“illegal aliens,” La Migra and local police agencies have

harassed and threatened Chicano communities throughout the Southwest.

More importantly, whenever Chicano organizing efforts — whether

in the fields or in the factories— have started to coalesce, the

green vans and buses of La Migra would soon appear on the scene to

cart off the agitators and all the sympathizers, if possible. Even the

fear of deportation has kept Chicanos from organizing at the workplace

and — in many instances — from registering family members

to vote here legally.

Over the past two years, several unions — notably the

International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU), the International

Longshoreman and Warehouseman’s Union (ILWU), the Retail Clerks, and

the United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers of

America — have begun to organize “all workers” among the

Chicano workforce in those industries where these unions are active.

For the “undocumented,” this has helped hasten the day when

they can achieve full rights in the workplace.The experience of the

ILGWU is typical. “More than 75 percent of our members are

Spanish speaking,” notes Christina Ramirez, an ILGWU organizer.

“And whenever we would start a campaign, the first thing the

employer would do is call La Migra. Several times, it would be the day

of a representation election and they’d show up and take away half

the workers.”Ramirez states that wages for workers in unorganized

shops rarely are above the minimum, with “undocumented” workers

typically receiving even less.“After Sbicca,” Ramirez

continues, “things have changed a lot. We’re advising workers

that they don’t even have to talk to immigration. It makes them feel

more secure and they’re not afraid to get involved. Also, the number

of raids has decreased and we’ve been more successful. Just this

week 125 workers at Motif Apparel went on strike. All of them are

‘undocumented.’ And they went back today — with

a victory.”

==

* Immigration raids; Sbicca shoe factory; Union Organizing; La

Migra;

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

INTERPRET THE WORLD AND CHANGE IT

Submit via web

[[link removed]]

Submit via email

Frequently asked questions

[[link removed]]

Manage subscription

[[link removed]]

Visit xxxxxx.org

[[link removed]]

Bluesky [[link removed]]

Facebook [[link removed]]

[link removed]

To unsubscribe, click the following link:

[link removed]

LABOR SOLIDARITY DEFENDS AGAINST DEPORTATIONS

[[link removed]]

In These Times Editors

November 24, 2025

In These Times

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

_ In 1978, immigrants won a long fight with U.S. Border Patrol after

a raid meant to union-bust. _

Los Angeles activists announce a meeting to recruit factory-based

committees to defend immigrant workers against raids by immigration

authorities., Courtesy of the Department of Special Collections,

Stanford University Libraries.

In 1978, amid deportations of undocumented workers in East Los

Angeles, one raid at the Sbicca shoe factory went differently: Lawyers

brought in by the AFL-CIO, which had been organizing at the factory,

were able to halt many of the deportations on Fourth Amendment

grounds. Larry Remer, for In These Times, detailed how the raids

impacted Mexican-American communities and how, in the Sbicca case,

labor solidarity helped in their defense.

The events described sound awfully familiar. Nationally, immigration

sweeps are still a common form of union-busting. And the labor

movement is still one of the strongest allies for undocumented

immigrants, helping organize anti-ICE responses in L.A., Chicago and

other cities.

In 1978, Larry Remer wrote:

East Los Angeles — Mariachi music drifts out from the cantinas

and the smell of chile and salsa fills the air. Nearly all

advertisements are in Spanish. So are the greetings from brown-skinned

passers-by. Were it not for the distinctively Southern California

stucco homes and wide-paved boulevards, this district could be

a shopping area in any major Latin American city.In fact, many people

consider East L.A. just that. With a population of more than one

million, the mini-metropolis of East L.A. serves as cultural capital

to the Chicano population of the southwestern U.S. East L.A. has its

own indigenous newspapers and radio stations, its own political power

structure, and its own burgeoning art and theater scene. Were it

a separate political entity, East L.A. would be the third largest

Spanish-speaking city in North America after Guadalajara and Mexico

City.But, in all things economic and political, East L.A.’s Chicanos

are in an inferior position compared to the whites who live in the

affluent suburban areas surrounding the barrio. This inequality is

aggravated by restrictive immigration statutes limiting the number of

Latinos permitted to enter the U.S. in search of work. Tens if not

hundreds of thousands enter illegally, many of whom are attracted to

East L.A. where they form an economic underclass of

“undocumented” workers and a large pool of exploitable, cheap

labor.Suddenly, however, one of the linchpins of this system of

exploitation is being subjected to a serious legal challenge. Backed

by labor unions frustrated in their efforts to organize Chicano

workers, a group of legal aid lawyers have thrown a monkey wrench

into the government’s ability to deport “undocumented”

workers. If their challenge is successful, both Chicano citizens and

undocumented workers will benefit from the restriction of the power of

the U.S. Border Patrol.When the lime green vans of La Migra — as

the Border Patrol is called — creep through East L.A., the

streets go quiet. Practically every Chicano can count a close friend

or relative among those vulnerable to summary arrest and deportation.

There are an estimated seven to ten million “undocumented”

workers living and working in the U.S. Each year, La Migra deports

more than 750,000 people. Yet more come. As part of their constant

search for aliens, La Migra periodically conducts massive sweeps

through Chicano communities, as well as raids on factories and

workplaces where aliens are believed to be employed.

SPECIAL POLICE FORCEKnowledge of illegal workers from Latin America

and elsewhere, living in barrios like East L.A., give La Migra its

excuse for constantly policing the Chicano community. Over the years,

the Border Patrol in the Southwest has emerged as a special police

force for suppressing the Chicano population. And it is this

harassment which is now under legal attack in the courts.The test case

arose from a raid by La Migra of the Sbicca shoe factory in South El

Monte. Last spring a force of 40 armed immigration officers

surrounded the factory and demanded that all employees produce their

immigration documents. In the sweep, “undocumented” workers

were arrested and taken to the L.A. INS office to be fingerprinted,

photographed, and put on a bus for Mexico.The raid was typical of

dozens conducted each month by La Migra in the Los Angeles area. Those

arrested were usually hurried out of the country so fast that by the

time they had been missed by friends or family they were on the other

side of the border.But the Sbicca raid turned out differently. For

several weeks, the Retail Clerks Union, AFL-CIO, had been organizing

at the shoe factory. As often happens, La Migra had been called by the

Sbicca management to rid the shop of unwanted union agitators. But

this time, before the workers had been put on the bus, one of the

union’s organizers brought in Peter Schey, an attorney with the

Legal Aid Foundation.Together with other lawyers from the ACLU, the

People’s College of Law, and the Los Angeles Center for Law and

Justice, Schey went to court to seek a restraining order to stop the

deportation. Their contention was that the Fourth Amendment rights of

the workers had been violated when — before they were

arrested — La Migra failed to advise them they were entitled to

an attorney and that what they said could be used against them.LAWYERS

WIN CASEThe court order was granted and INS was ordered to stop the

buses. Then, Schey and several other lawyers met with the workers to

advise them of their rights and to offer their assistance. Of those

arrested, 65 decided to fight deportation.

Before Sbicca, deportation hearings were typically handled quickly and

efficiently. “Undocumented” workers who, by their own

admission, lacked the proper permission for entering the U.S.,

typically did not even bother to fight the proceedings. Told that they

could either be immediately expelled from the U.S. or — if they

chose to fight — formally deported, in which case they would be

jailed the next time they were apprehended inside the U.S., just about

everyone chose immediate expulsion. Once released inside Mexico, they

would painstakingly begin the process of sneaking back into the U.S.

and getting established in a new job all over again.

But the attorneys for the “Sbicca 65” attempted a new

strategy. Assured that previous admissions to Border Patrol officers

would be inadmissible, they instructed their clients to invoke the

Fifth Amendment when questioned about their status, place of birth,

and length of time spent in the U.S. This forced immigration officials

to ask representatives of the U.S. State Department to travel to the

workers’ hometowns and search for their birth certificates to prove

that these peo- ple were born in Mexico and therefore not legally in

the U.S.The State Department not only lacked the staff to cooperate

fully with La Migra, but even when it tried to obtain records, the

cities of rural Mexico where most of the workers are said to be from

proved too far-flung and record keeping there too inexact to produce

any useful material.Thus far, nearly half the Sbicca cases have been

dismissed for lack of evidence. Moreover, the hearing process has

forced immigration officials to bring their other activities in L.A.

to a halt.The Sbicca attorneys are optimistic that they can force La

Migra to abandon altogether their factory raids and street sweeps.

Notes Mark Rosenbaum of the ACLU, “I can’t understand why

nobody realized this before. These are people, not cattle. And they

have the same rights against self-incrimination as you or I or

anybody else.”

UNIONS FIGHT DEPORTATIONHowever, the most significant development in

the Sbicca case has been the emergence of organized labor as a force

on behalf of “undocumented” workers. The existence of two

categories of workers — those with documents and those

without — has been the principal dynamic in the exploitation of

Chicanos in the U.S. Under the guise of searching for so-called

“illegal aliens,” La Migra and local police agencies have

harassed and threatened Chicano communities throughout the Southwest.

More importantly, whenever Chicano organizing efforts — whether

in the fields or in the factories— have started to coalesce, the

green vans and buses of La Migra would soon appear on the scene to

cart off the agitators and all the sympathizers, if possible. Even the

fear of deportation has kept Chicanos from organizing at the workplace

and — in many instances — from registering family members

to vote here legally.

Over the past two years, several unions — notably the

International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU), the International

Longshoreman and Warehouseman’s Union (ILWU), the Retail Clerks, and

the United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers of

America — have begun to organize “all workers” among the

Chicano workforce in those industries where these unions are active.

For the “undocumented,” this has helped hasten the day when

they can achieve full rights in the workplace.The experience of the

ILGWU is typical. “More than 75 percent of our members are

Spanish speaking,” notes Christina Ramirez, an ILGWU organizer.

“And whenever we would start a campaign, the first thing the

employer would do is call La Migra. Several times, it would be the day

of a representation election and they’d show up and take away half

the workers.”Ramirez states that wages for workers in unorganized

shops rarely are above the minimum, with “undocumented” workers

typically receiving even less.“After Sbicca,” Ramirez

continues, “things have changed a lot. We’re advising workers

that they don’t even have to talk to immigration. It makes them feel

more secure and they’re not afraid to get involved. Also, the number

of raids has decreased and we’ve been more successful. Just this

week 125 workers at Motif Apparel went on strike. All of them are

‘undocumented.’ And they went back today — with

a victory.”

==

* Immigration raids; Sbicca shoe factory; Union Organizing; La

Migra;

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

INTERPRET THE WORLD AND CHANGE IT

Submit via web

[[link removed]]

Submit via email

Frequently asked questions

[[link removed]]

Manage subscription

[[link removed]]

Visit xxxxxx.org

[[link removed]]

Bluesky [[link removed]]

Facebook [[link removed]]

[link removed]

To unsubscribe, click the following link:

[link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Portside

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a