|

|

A future without customers? The AI boom’s hidden flaw

If everyone gets replaced with AI, why do you need to buy AI?

The Capitalist is a reader-supported publication

Reject Corporate Left Wing Journalism

In the summer of 2023, a small law firm in Chicago makes a quiet but seismic decision. Facing rising costs and competitive pressure, the firm subscribed to an enterprise version of ChatGPT, the AI model developed by OpenAI.

Within months, the software had streamlined document review, legal research, and even client correspondence. The catch? The firm, which once employed 15 paralegals, now needed only two, whose sole job it is to feed their fallen co-workers workload into “the machine.”

The rest were let go, their roles absorbed by an algorithm that worked faster, cheaper, and—arguably—better. Or as a brave young man once famously said to a young girl “can’t be bargained with, can’t be reasoned with. It doesn’t feel pity, or remorse, or fear. And it absolutely will not stop... ever”

This story, shortly to be replicated across countless industries, reveals a troubling paradox at the heart of the AI revolution: the technology has likely passed the point of cannibalizing the very customers it was meant to aid and (more importantly, which is not being talked about at all by anyone) bought by.

The AI industry is racing forward with breathtaking ambition. Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, has articulated a vision to own the “full stack” of AI— From making custom chips and building data centers, to creating the models and agents that run on them. Altman is even looking at building smartphones, browsers and wearables using his OpenAI tech.

Tinnitus Discovery Leaves Doctors Speechless (Try Tonight)

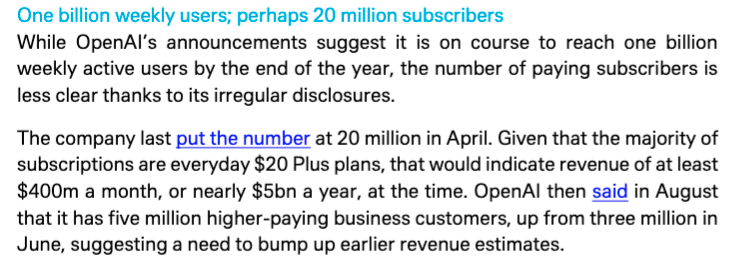

Yet, a recent report from Deutsche Bank Research paints a sobering picture of the industry’s financial trajectory. In Europe, the growth of paying AI accounts is stalling, with subscription rates showing a trend line down.

Deutsche Bank Research reports that:

All that maybe true, but that trend line still exists:

The trend line is not a disaster, at least not yet, but it is very clearly moving down. Open AI remains bullish on its corporate customers and enterprise accounts but the core issue of how AI will generate sustainable revenue is still…vague. Altman himself has commented on this saying “We will have to monetize it somehow at some point. The compute costs are eye-watering”

“Some how” and “At some point” are concerning phrases. Especially when there is a bulk of evidence emerging that individual AI subscriptions are not fitting in to an easily marketable solution for private consumers.

Unlike the iPhone, which sold billions of units by creating a new consumer market, AI has not lent itself to mass individual subscriptions so far. Quite the opposite in fact.

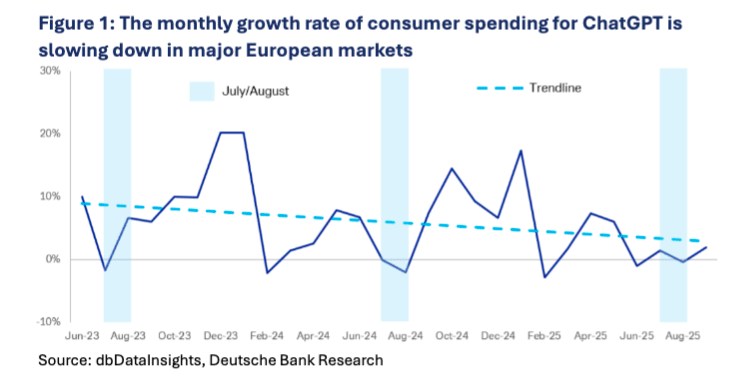

Netflix’s or Spotify’s streaming model, another oft-cited analogy, also falters: while it can generate cat videos or write code, AI’s most transformative application is in enterprise settings, where a single license can replace entire floors of people.

AI is not Grammerly. It doesnt help make you a better writer. It is not like autocorrect on a phone that helps corrects your spelling. It is fast becoming apparent that AI is not here to help you become better at what you do at all, it is here to replace you, and your colleagues, and what you all do … entirely.

Let’s consider the Chicago law firm example again. In a hypothetical world, each of those 15 original paralegals might have subscribed to ChatGPT to enhance their work (think Grammerly), creating 15 customers. In reality, the firm became the sole customer, slashing its workforce and leaving 13 potential users unemployed. This pattern repeats across industries as diverse as banking, coding, and writing. Far from assisting people in their jobs, AI’s efficiency eliminates the jobs of its most likely adopters because, it turns out, the human component of the equation is the weak link and the machine does better without them.

This cannibalization is not a distant threat but a present reality. Estimates vary but some believe that generative AI could automate tasks equivalent to 30% of current white-collar jobs in developed economies within a decade. The same technology that empowers a coder to debug faster or a writer to draft quicker also renders their individual roles redundant when scaled. The societal implications are obviously profound, but the economic paradox is as equally stark.

AI’s early adopters—professionals in knowledge-based industries—are increasingly replaced by the tool they once championed as a transformative enhancement of their value. The result is a shrinking pool of individual subscribers, as companies consolidate AI use into fewer and fewer, high-cost enterprise licenses.

AI’s next frontier—conversational agents capable of passing the Turing test, where a machine’s responses are truly indistinguishable from a human’s—looms closer than many realize.

Alan Turing proposed the original benchmark in 1950, imagining a future where machines could convincingly mimic human dialogue. Sam Altman has argued that the original measurement of the Turing test has been surpassed and that the “Turing Test 2.0” is when AI can “do science” on its own.

He may well be correct on the original definition of the Turing test having been passed. If you have ever stumbled into the comment sections of any of the AI generated E-girl influencers on Instagram, you would be forgiven for arguing that the Turing test has long since been consigned to history, given the way the commenters converse (and flirt) with a computer sprite. (Altman himself certainly appears to believe this with his controversial upcoming plans for “erotic content” in ChatGPT.)

However if he is correct with his assertion that soon AI will be able to make scientific breakthroughs on its own, you may soon be able to add “Scientist” next to paralegal and coder in the jobless column.

As AI moves from text to speech, its reach will expand even further. When you call customer service, you’ll speak to an AI. When you visit a bank, an AI will process your loan. These interactions, seamless and cost-effective for businesses, will further erode the need for human employees.

Humans will certainly interact with AI, they will likely interact with AI a lot, but as individuals through corporate portals rather than by purchasing personal OpenAI subscriptions.

If AI continues to displace its potential consumer base as the trend line is beginning to suggest, companies like OpenAI may find themselves with cutting-edge technology but no mass market to sell it to.

The Deutsche Bank report warns that the AI industry’s current trajectory assumes widespread consumer uptake, but that may never emerge and if it does it may not arrive soon enough to save OpenAI from the skyscraper of debt they will have built for themselves and they are not the only ones in this boat.

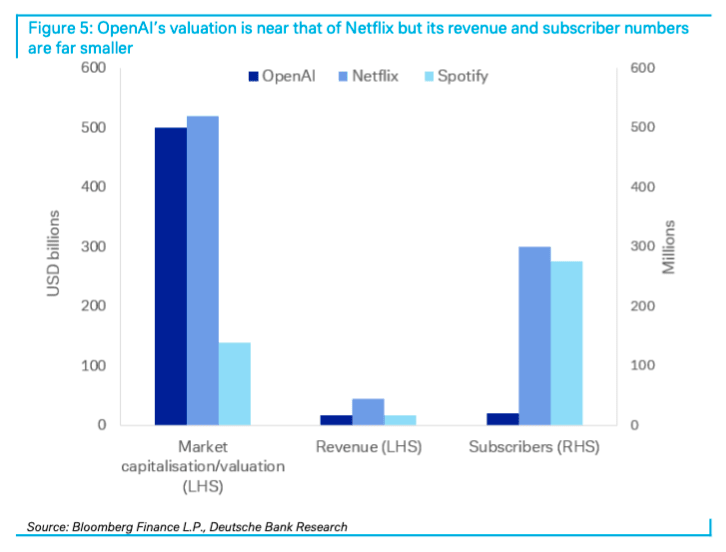

For a populace that will soon be surrounded by AI in nearly everything they touch, the “it” factor, the “need” to subscribe personally to ChatGPT in particular just isn’t there yet.

For the unemployed paralegal, coder, or call center worker sitting idly on the couch, the ability to make AI-generated cat videos may replace doom scrolling TikTok, but even then, the number of subscribers from that is unlikely to cover the “eye watering compute costs” invested so far.

If this all sounds familiar it’s because this dynamic echoes one of the great historical missteps in business: the collapse of Nortel Networks in the early 2000s.

Nortel, a telecommunications giant, overestimated demand for its optical switches, betting on an internet boom that never materialized at the scale and in the direction it predicted. While the internet did indeed eventually take over the world, it didn’t help Nortel. By 2001, Nortel were going through their Icarus moment, the company’s valuation plummeted towards it eventual demise, leaving in its wake a cautionary tale of overconfidence in future technological adoption.

History says that OpenAI risks a similar fate. Take for example “Internet on your phone.”

“Mobile Browsing” was launched in the early 2000’s with GPRS technology, but did not take off. Even with the widespread deployment of (and massive investment in) 3G technology in the mid 2000’s, it wasn’t until the original iPhone (launched in 2007) that “internet on your phone” captured the publics imagination. Even then, at it’s launch Steve Job’s announcement of “A breakthrough Internet communications device“ (2:06) met with barely a smattering of applause.

(Ironic considering that the two announcements that received the biggest cheers and applause were “A widescreen Ipod with touch controls“ (1:36) and “A Revolutionary mobile phone“ (1:52) two things most of us barely use our phones for anymore.)

What does this mean for AI’s future?

The industry’s current path—massive investments in infrastructure with uncertain returns—suggests a bubble that could rival Nortel’s, and not to compound the issues but there are two other nasty looking storm clouds on the horizon for AI in general and OpenAI in particular.

Operationally the hardware underpinning AI’s rise—specialized chips like NVIDIA’s H100—faces a replacement cycle measured in just two to three years. Every upgrade to the next generation demands billions in capital expenditure. OpenAI’s projected $60 billion annual spend on Oracle’s data centers alone underscores the scale of this investment. (Thats more than the GDP of Jordan according to the IMF)

That financial avalanche could bury even the most optimistic projections if the anticipated consumer base fails to materialize. Also, remember that it took nearly 7 years before “Internet on your phone” became “a thing.” At current replacement rates, Open AI’s costs by that point could be larger than the GDP of some developed nations!

The other storm cloud is the market mechanism. For now OpenAI can charge high prices for enterprise clients but those prices are only going to go one way. Down. Technology will get cheaper, emerging competition will drive down the cost of services further still.

OpenAI may be the poster child for the tech revolution right now but very few of the firms that held claim to that title in late 1999 appear as anything other than footnotes in the history of the internet today. AOL, Netscape, Nortel, even Microsoft’s Internet Explorer, once the de facto gateway to the internet for a generation, is now just a memory.

For now, the Chicago law firm’s story is a microcosm of a larger reckoning. The paralegals who lost their jobs aren’t buying AI subscriptions; their priority is searching for new (AI free) careers.

As AI’s capabilities grow, so does its potential to reshape society—not as a democratizing force, but as a debt laden paradox that enriches a few while leaving many behind.

The question is not whether AI can pass the Turing test, but whether it can pass a more human one: creating a future where technology serves society, not just itself.

A Terminator with a heart, as it were.

The Capitalist is a reader-supported publication

Reject Corporate Left Wing Journalism

You're currently a free subscriber to The Capitalist. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription.