Email

Ideas for Pension Reform

| From | Institute of Economic Affairs <[email protected]> |

| Subject | Ideas for Pension Reform |

| Date | September 4, 2025 7:00 AM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

View this post on the web at [link removed]

By Professor Len Shackleton, Editorial and Research Fellow

The state pension is a big issue. It currently costs upwards of £140 billion a year, paid to 13 million pensioners. Both of these numbers are, on current trends, expected to rise; in the case of the former by up to £40 million in today’s money by 2050.

Institute of Economic Affairs | Insider is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

This is seen as an intolerable burden, particularly by today’s young. They see themselves, hard-pressed with poorly-paying jobs (if they can get one), student loan repayments, high rents and so forth, as subsidising idle mortgage-free retirees on perpetual Saga holidays. A majority apparently believe that they will themselves never receive similar pensions, which will have been scrapped long before they reach their dotage.

More rationally, it is pointed out that the state pension is no longer, if it ever was, paid for by national insurance contributions – which are today just a complicated extension of income tax. The belief amongst today’s retired that they have ‘earned’ their pensions by their contributions is, ruder critics say, a self-serving fallacy. Today’s pensions are always paid by today’s taxpayers (though to be fair that group now includes two-thirds of pensioners). State pensions are really just another form of welfare benefit, and should not be spared from attempts to cut ever-growing state spending.

Of course, we have raised the age at which you are entitled to a state pension. This helps. Now set at 66, SPA is planned to rise further, to 67 by 2028 and 68 in the 2040s. This process could be accelerated, with the pension age pushed still higher if life expectancy rises. There are limits to this as a strategy for containing costs. Older workers have health problems, and even fit workers may find it difficult to get work. Many will have to fall back on other benefits, which may be more generous than the state pension, so reducing the savings to the taxpayer.

One proposal from GenZers in thinktanks and on social media is to means-test the state pension. Well, good luck with that one. As we saw with the attempt to cut back on the relatively trivial winter fuel allowance, there would be tremendous political hostility if any government was bold enough to try it. And, as so often with apparently simple solutions to policy issues, there would be knock-on consequences. Although pensioner poverty is now much less serious an issue than in the past, there are still many pensioners whose overall income is only marginally above the poverty line because they have not been able to save sufficiently during their working (or non-working) life. We need to incentivise young people to make whatever savings they can; means-testing state pensions would have the opposite effect.

Another way to reduce the cost of pensions is to adjust the eligibility criteria. The state pension is not automatic for those reaching 66. Although national insurance contributions don’t pay into a fund for retirement, having made contributions is a necessary criterion for receiving the pension. People are not wilfully confused about NICs: few people understand it. The system is not straightforward.

When I was first employed I had a physical card (image below). Each week the employer put a stamp on it to show NICs had been paid. If you lost your job, you ‘got your cards’ to take to the next employer or the Labour Exchange (not ‘Job Centre’ back then). From the mid-70s NICs became computerised, but the principle remained.

These contributions matter. At the moment you need a full 35 years of contributions to receive a full pension; if you have fewer years, your pension is reduced pro rata. You need ten years of contributions to get any pension at all.

Of those who do receive a state pension, about half receive less than the full amount: not a lot of people know this. It suggests a way in which pension spending could be reduced. In the recent past, as a male you needed 44 years of contributions to receive a pension at 65; a woman needed to have paid in for 39 years to get a pension at 60. Even in France, where pensions are payable at 62, you need 43 years in the system to get a full pension. So the 35 years, particularly with a rising SPA, is not a big ask – particularly as there are various credits if you are not working through caring responsibilities, illness and so on.

So we could conceivably phase in a requirement for, say, 40 years of contributions to receive a full pension and fifteen years to get any pension. It wouldn’t affect current pensions in payment, but it would over time reduce the amount paid out. The main sufferers would probably be recent migrants.

The other, more significant, way in which we could control future spending is through changing the basis on which we uprate pensions. A little history on this may help.

Although state pensions date back to the Liberal government of the first years of the twentieth century, the modern pension began with the Beveridge Plan of the 1940s. Beveridge aimed to set the pension at a ‘subsistence minimum’. But, having experienced falling prices in the interwar years, he didn’t plan – and subsequent legislation didn’t allow for – postwar inflation. In practice, until the mid-1970s increases in the state pension were discretionary and unsystematic. In periods of economic downturn, pensioners might experience a fall in real income.

The Labour government of 1974-79 changed this, with a statutory annual increase based on the higher of RPI inflation or the rate of increase of average earnings. The Thatcher government switched to uprating simply in line with inflation. The value of the state pension fell in relation to average earnings as a result, but the average living standards of pensioners rose as a result of an increase in private pensions (still mainly based on final salary at that time), savings and earnings during retirement.

From 1997, the Blair government increased pensions by inflation or 2.5%, whichever was the higher, and then finally the Coalition government introduced the ‘triple lock’; the highest of 2.5%, the increase in average earnings or CPI inflation.

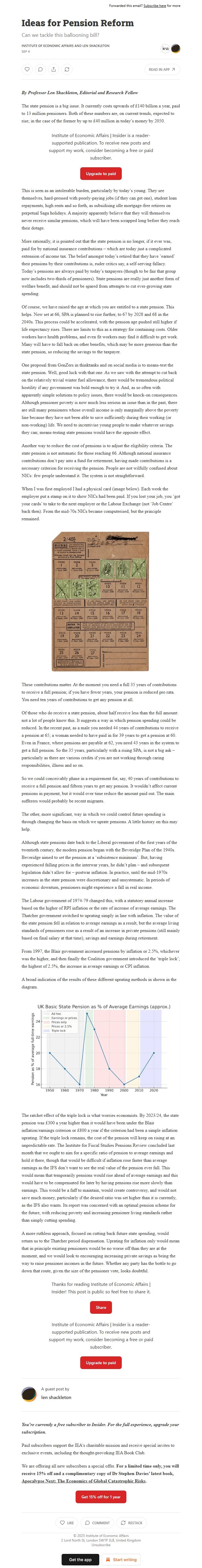

A broad indication of the results of these different uprating methods in shown in the diagram.

The ratchet effect of the triple lock is what worries economists. By 2023/24, the state pension was £300 a year higher than it would have been under the Blair inflation/earnings criterion or £800 a year if the criterion had been a simple inflation uprating. If the triple lock remains, the cost of the pension will keep on rising at an unpredictable rate. The Institute for Fiscal Studies Pensions Review concluded last month that we ought to aim for a specific ratio of pension to average earnings and hold it there, though that would be difficult if inflation rose faster than average earnings as the IFS don’t want to see the real value of the pension ever fall. This would mean that temporarily pensions would rise ahead of average earnings and this would have to be compensated for later by having pensions rise more slowly than earnings. This would be a faff to maintain, would create controversy, and would not save much money, particularly if the desired ratio was set higher than it is currently, as the IFS also wants. Its report was concerned with an optimal pension scheme for the future, with reducing poverty and increasing pensioner living standards rather than simply cutting spending.

A more ruthless approach, focused on cutting back future state spending, would return us to the Thatcher period dispensation. Uprating for inflation only would mean that in principle existing pensioners would be no worse off than they are at the moment, and we would look to encouraging increasing private savings as being the way to raise pensioner incomes in the future. Whether any party has the bottle to go down that route, given the size of the pensioner vote, looks doubtful.

Thanks for reading Institute of Economic Affairs | Insider! This post is public so feel free to share it.

Institute of Economic Affairs | Insider is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Unsubscribe [link removed]?

By Professor Len Shackleton, Editorial and Research Fellow

The state pension is a big issue. It currently costs upwards of £140 billion a year, paid to 13 million pensioners. Both of these numbers are, on current trends, expected to rise; in the case of the former by up to £40 million in today’s money by 2050.

Institute of Economic Affairs | Insider is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

This is seen as an intolerable burden, particularly by today’s young. They see themselves, hard-pressed with poorly-paying jobs (if they can get one), student loan repayments, high rents and so forth, as subsidising idle mortgage-free retirees on perpetual Saga holidays. A majority apparently believe that they will themselves never receive similar pensions, which will have been scrapped long before they reach their dotage.

More rationally, it is pointed out that the state pension is no longer, if it ever was, paid for by national insurance contributions – which are today just a complicated extension of income tax. The belief amongst today’s retired that they have ‘earned’ their pensions by their contributions is, ruder critics say, a self-serving fallacy. Today’s pensions are always paid by today’s taxpayers (though to be fair that group now includes two-thirds of pensioners). State pensions are really just another form of welfare benefit, and should not be spared from attempts to cut ever-growing state spending.

Of course, we have raised the age at which you are entitled to a state pension. This helps. Now set at 66, SPA is planned to rise further, to 67 by 2028 and 68 in the 2040s. This process could be accelerated, with the pension age pushed still higher if life expectancy rises. There are limits to this as a strategy for containing costs. Older workers have health problems, and even fit workers may find it difficult to get work. Many will have to fall back on other benefits, which may be more generous than the state pension, so reducing the savings to the taxpayer.

One proposal from GenZers in thinktanks and on social media is to means-test the state pension. Well, good luck with that one. As we saw with the attempt to cut back on the relatively trivial winter fuel allowance, there would be tremendous political hostility if any government was bold enough to try it. And, as so often with apparently simple solutions to policy issues, there would be knock-on consequences. Although pensioner poverty is now much less serious an issue than in the past, there are still many pensioners whose overall income is only marginally above the poverty line because they have not been able to save sufficiently during their working (or non-working) life. We need to incentivise young people to make whatever savings they can; means-testing state pensions would have the opposite effect.

Another way to reduce the cost of pensions is to adjust the eligibility criteria. The state pension is not automatic for those reaching 66. Although national insurance contributions don’t pay into a fund for retirement, having made contributions is a necessary criterion for receiving the pension. People are not wilfully confused about NICs: few people understand it. The system is not straightforward.

When I was first employed I had a physical card (image below). Each week the employer put a stamp on it to show NICs had been paid. If you lost your job, you ‘got your cards’ to take to the next employer or the Labour Exchange (not ‘Job Centre’ back then). From the mid-70s NICs became computerised, but the principle remained.

These contributions matter. At the moment you need a full 35 years of contributions to receive a full pension; if you have fewer years, your pension is reduced pro rata. You need ten years of contributions to get any pension at all.

Of those who do receive a state pension, about half receive less than the full amount: not a lot of people know this. It suggests a way in which pension spending could be reduced. In the recent past, as a male you needed 44 years of contributions to receive a pension at 65; a woman needed to have paid in for 39 years to get a pension at 60. Even in France, where pensions are payable at 62, you need 43 years in the system to get a full pension. So the 35 years, particularly with a rising SPA, is not a big ask – particularly as there are various credits if you are not working through caring responsibilities, illness and so on.

So we could conceivably phase in a requirement for, say, 40 years of contributions to receive a full pension and fifteen years to get any pension. It wouldn’t affect current pensions in payment, but it would over time reduce the amount paid out. The main sufferers would probably be recent migrants.

The other, more significant, way in which we could control future spending is through changing the basis on which we uprate pensions. A little history on this may help.

Although state pensions date back to the Liberal government of the first years of the twentieth century, the modern pension began with the Beveridge Plan of the 1940s. Beveridge aimed to set the pension at a ‘subsistence minimum’. But, having experienced falling prices in the interwar years, he didn’t plan – and subsequent legislation didn’t allow for – postwar inflation. In practice, until the mid-1970s increases in the state pension were discretionary and unsystematic. In periods of economic downturn, pensioners might experience a fall in real income.

The Labour government of 1974-79 changed this, with a statutory annual increase based on the higher of RPI inflation or the rate of increase of average earnings. The Thatcher government switched to uprating simply in line with inflation. The value of the state pension fell in relation to average earnings as a result, but the average living standards of pensioners rose as a result of an increase in private pensions (still mainly based on final salary at that time), savings and earnings during retirement.

From 1997, the Blair government increased pensions by inflation or 2.5%, whichever was the higher, and then finally the Coalition government introduced the ‘triple lock’; the highest of 2.5%, the increase in average earnings or CPI inflation.

A broad indication of the results of these different uprating methods in shown in the diagram.

The ratchet effect of the triple lock is what worries economists. By 2023/24, the state pension was £300 a year higher than it would have been under the Blair inflation/earnings criterion or £800 a year if the criterion had been a simple inflation uprating. If the triple lock remains, the cost of the pension will keep on rising at an unpredictable rate. The Institute for Fiscal Studies Pensions Review concluded last month that we ought to aim for a specific ratio of pension to average earnings and hold it there, though that would be difficult if inflation rose faster than average earnings as the IFS don’t want to see the real value of the pension ever fall. This would mean that temporarily pensions would rise ahead of average earnings and this would have to be compensated for later by having pensions rise more slowly than earnings. This would be a faff to maintain, would create controversy, and would not save much money, particularly if the desired ratio was set higher than it is currently, as the IFS also wants. Its report was concerned with an optimal pension scheme for the future, with reducing poverty and increasing pensioner living standards rather than simply cutting spending.

A more ruthless approach, focused on cutting back future state spending, would return us to the Thatcher period dispensation. Uprating for inflation only would mean that in principle existing pensioners would be no worse off than they are at the moment, and we would look to encouraging increasing private savings as being the way to raise pensioner incomes in the future. Whether any party has the bottle to go down that route, given the size of the pensioner vote, looks doubtful.

Thanks for reading Institute of Economic Affairs | Insider! This post is public so feel free to share it.

Institute of Economic Affairs | Insider is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Unsubscribe [link removed]?

Message Analysis

- Sender: n/a

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: n/a

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a