Email

2024 FFP “State of the Program” Report — Part 2: Measuring the Fair Food difference in the fields

| From | Coalition of Immokalee Workers <[email protected]> |

| Subject | 2024 FFP “State of the Program” Report — Part 2: Measuring the Fair Food difference in the fields |

| Date | July 31, 2025 2:49 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

[[link removed]]

[link removed] [[link removed]]

Workers take a rest break under shade on a Fair Food Program participating farm

Fair Food Program reaches major landmark: Over $50 million in Fair Food Premium — aka the “Penny per Pound” — has been paid by Participating Buyers to improve farmworkers’ income on participating farms.

2024 SOTP: “The [compliance] data demonstrates that Participating Growers across the Program have developed a deep commitment to the FFP’s joint complaint resolution process, driven by the recognition that workers frequently have valuable insight into workplace practices and related risks.”

In part 2 of our series on the release of the 2024 Fair Food Program State of the Program report, we’re going to focus on what truly sets the FFP apart in agriculture: Results. Concrete results.

[To download the 2024 SOTP report in its entirety, click here! [[link removed]] ]

Distinct from any other social certification program in the world today, the foundation of the FFP is rooted in the CIW’s legally binding agreements with Participating Buyers, some of the world’s largest corporations that agree to purchase preferentially from farms that meet the standards required by the Fair Food Code of Conduct — and to suspend purchases from farms that are suspended from the Program — as verified by the Program’s dedicated monitoring organization, the Fair Food Standards Council (FFSC). Farms that are suspended from the Program for non-compliance cannot sell their product to Participating Buyers during the suspension period and until corrective actions are implemented and verified through a re-entry audit.

Apart from the Program’s purchasing requirements, the Fair Food Premium paid by buyers also helps to supplement wages unduly suppressed by market pressure. Motivated by these market incentives, Participating Growers agree to implement the Fair Food Code of Conduct on their farms, to refrain from intimidation or retaliation against workers who use the Program’s complaint mechanism, to cooperate with complaint investigations and audits by the FFSC, and to distribute the Fair Food Premium to their workers.

The FFP’s monitoring and enforcement mechanisms are also unique and designed to ensure that the Program’s standards are fully implemented on all participating farms. Based on their own experiences as workers, CIW leaders understood that multiple interconnected mechanisms would be necessary to establish the fullest visibility possible into Participating Growers’ operations and to ensure compliance with the Program’s standards. Those mechanisms include a Code of Conduct that is based on workers’ priorities and experiences in the workplace; worker‑to‑worker education on their rights and responsibilities under the Code that prepares workers to serve as frontline monitors of their own rights; a 24/7 complaint investigation and resolution process where workers can report violations free from the fear of retaliation; and regular, comprehensive farm audits. These elements, none of which is sufficient alone, are all backed by the Program’s market-based incentives and work in coordination to protect workers from exploitation and provide a work environment of respect and dignity.

Today, we want to share just how transformative the FFP has been for the tens of thousands of farmworkers on participating farms, using both qualitative and quantitative measures to demonstrate the concrete changes forged on participating farms — owing much, as always, to the unique partnership with Participating Growers at the heart of the Fair Food Program.

As detailed in this report, farmworkers, growers, and buyers have all lauded the FFP’s best-in-class protections. In the words of one worker speaking with FFSC auditors, “We are comfortable, now we can speak [up] without fear [of retaliation].” Another said simply, “You motivate me to have no fear.”

But workers are not alone in seeing the extraordinary value of the FFP on participating farms. Reflecting on the Program, and the history of abuse in the agricultural industry, Gwen Cameron, co-owner of FFP partner farm Rancho Durazno in Palisade, CO, shared, “I hope those types of abuses are not happening, but the point is, we don’t know. That’s what [this Program] is for.” Jon Esformes, CEO of Sunripe Certified Brands and the first grower to join the Fair Food Program in 2010, said: “There was no question in my mind that bad things were happening in agriculture and on farms, not just my own, but farms across the country — things that I did not know about and had no mechanism to find out about. This gave me the tool.”

Meanwhile Theresa Chester, Director of Purchasing at Bon Appétit, a Participating Buyer in the Program, told a reporter [[link removed]] from the Miami Herald: “Through our purchasing powers and our purchasing orders that go to the program, the issue of workers’ rights is brought to that same level of food safety… Respect for workers is just as important as the food safety we bring to the table. It brings us peace of mind that our supply chain is free of those typical abuses.”

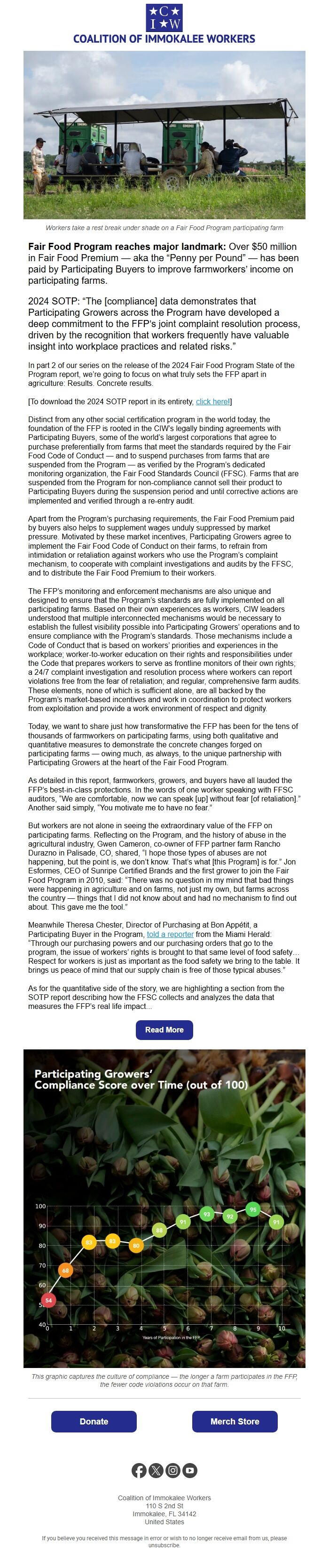

As for the quantitative side of the story, we are highlighting a section from the SOTP report describing how the FFSC collects and analyzes the data that measures the FFP’s real life impact...

Read More [[link removed]]

[link removed] [[link removed]]

This graphic captures the culture of compliance — the longer a farm participates in the FFP, the fewer code violations occur on that farm.

Donate [[link removed]] Merch Store [[link removed]]

[link removed] [[link removed]] [link removed] [[link removed]] [link removed] [[link removed]] [link removed] [[link removed]]

Coalition of Immokalee Workers

110 S 2nd St

Immokalee, FL 34142

United States

If you believe you received this message in error or wish to no longer receive email from us, please unsubscribe: [link removed] .

[link removed] [[link removed]]

Workers take a rest break under shade on a Fair Food Program participating farm

Fair Food Program reaches major landmark: Over $50 million in Fair Food Premium — aka the “Penny per Pound” — has been paid by Participating Buyers to improve farmworkers’ income on participating farms.

2024 SOTP: “The [compliance] data demonstrates that Participating Growers across the Program have developed a deep commitment to the FFP’s joint complaint resolution process, driven by the recognition that workers frequently have valuable insight into workplace practices and related risks.”

In part 2 of our series on the release of the 2024 Fair Food Program State of the Program report, we’re going to focus on what truly sets the FFP apart in agriculture: Results. Concrete results.

[To download the 2024 SOTP report in its entirety, click here! [[link removed]] ]

Distinct from any other social certification program in the world today, the foundation of the FFP is rooted in the CIW’s legally binding agreements with Participating Buyers, some of the world’s largest corporations that agree to purchase preferentially from farms that meet the standards required by the Fair Food Code of Conduct — and to suspend purchases from farms that are suspended from the Program — as verified by the Program’s dedicated monitoring organization, the Fair Food Standards Council (FFSC). Farms that are suspended from the Program for non-compliance cannot sell their product to Participating Buyers during the suspension period and until corrective actions are implemented and verified through a re-entry audit.

Apart from the Program’s purchasing requirements, the Fair Food Premium paid by buyers also helps to supplement wages unduly suppressed by market pressure. Motivated by these market incentives, Participating Growers agree to implement the Fair Food Code of Conduct on their farms, to refrain from intimidation or retaliation against workers who use the Program’s complaint mechanism, to cooperate with complaint investigations and audits by the FFSC, and to distribute the Fair Food Premium to their workers.

The FFP’s monitoring and enforcement mechanisms are also unique and designed to ensure that the Program’s standards are fully implemented on all participating farms. Based on their own experiences as workers, CIW leaders understood that multiple interconnected mechanisms would be necessary to establish the fullest visibility possible into Participating Growers’ operations and to ensure compliance with the Program’s standards. Those mechanisms include a Code of Conduct that is based on workers’ priorities and experiences in the workplace; worker‑to‑worker education on their rights and responsibilities under the Code that prepares workers to serve as frontline monitors of their own rights; a 24/7 complaint investigation and resolution process where workers can report violations free from the fear of retaliation; and regular, comprehensive farm audits. These elements, none of which is sufficient alone, are all backed by the Program’s market-based incentives and work in coordination to protect workers from exploitation and provide a work environment of respect and dignity.

Today, we want to share just how transformative the FFP has been for the tens of thousands of farmworkers on participating farms, using both qualitative and quantitative measures to demonstrate the concrete changes forged on participating farms — owing much, as always, to the unique partnership with Participating Growers at the heart of the Fair Food Program.

As detailed in this report, farmworkers, growers, and buyers have all lauded the FFP’s best-in-class protections. In the words of one worker speaking with FFSC auditors, “We are comfortable, now we can speak [up] without fear [of retaliation].” Another said simply, “You motivate me to have no fear.”

But workers are not alone in seeing the extraordinary value of the FFP on participating farms. Reflecting on the Program, and the history of abuse in the agricultural industry, Gwen Cameron, co-owner of FFP partner farm Rancho Durazno in Palisade, CO, shared, “I hope those types of abuses are not happening, but the point is, we don’t know. That’s what [this Program] is for.” Jon Esformes, CEO of Sunripe Certified Brands and the first grower to join the Fair Food Program in 2010, said: “There was no question in my mind that bad things were happening in agriculture and on farms, not just my own, but farms across the country — things that I did not know about and had no mechanism to find out about. This gave me the tool.”

Meanwhile Theresa Chester, Director of Purchasing at Bon Appétit, a Participating Buyer in the Program, told a reporter [[link removed]] from the Miami Herald: “Through our purchasing powers and our purchasing orders that go to the program, the issue of workers’ rights is brought to that same level of food safety… Respect for workers is just as important as the food safety we bring to the table. It brings us peace of mind that our supply chain is free of those typical abuses.”

As for the quantitative side of the story, we are highlighting a section from the SOTP report describing how the FFSC collects and analyzes the data that measures the FFP’s real life impact...

Read More [[link removed]]

[link removed] [[link removed]]

This graphic captures the culture of compliance — the longer a farm participates in the FFP, the fewer code violations occur on that farm.

Donate [[link removed]] Merch Store [[link removed]]

[link removed] [[link removed]] [link removed] [[link removed]] [link removed] [[link removed]] [link removed] [[link removed]]

Coalition of Immokalee Workers

110 S 2nd St

Immokalee, FL 34142

United States

If you believe you received this message in error or wish to no longer receive email from us, please unsubscribe: [link removed] .

Message Analysis

- Sender: Coalition of Immokalee Workers

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: Florida Immokalee, Florida

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- EveryAction