| From | xxxxxx <[email protected]> |

| Subject | A Vietnam Story: From Othering to Solidarity |

| Date | May 3, 2025 12:35 AM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

[[link removed]]

A VIETNAM STORY: FROM OTHERING TO SOLIDARITY

[[link removed]]

JJ Johnson

April 29, 2025

Washington Spectator

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

_ Fifty years after the end of the Vietnam War, JJ Johnson reflects

on the journey that led him, along with two fellow Fort Hood soldiers,

to refuse orders to Vietnam and on our situation today, "the darkest

period in my lifetime." _

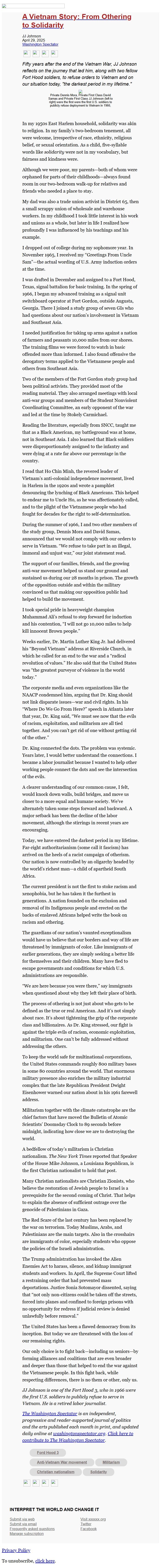

Private Dennis Mora, Private First Class David Samas and Private

First Class JJ Johnson (left to right) were the first were the first

U.S. soldiers to publicly refuse deployment to Vietnam in 1966,

In my 1950s East Harlem household, solidarity was akin to religion. In

my family’s two-bedroom tenement, all were welcome, irrespective of

race, ethnicity, religious belief, or sexual orientation. As a child,

five-syllable words like _solidarity_ were not in my vocabulary, but

fairness and kindness were.

Although we were poor, my parents—both of whom were orphaned for

parts of their childhoods—always found room in our two-bedroom

walk-up for relatives and friends who needed a place to stay.

My dad was also a trade union activist in District 65, then a small

scrappy union of wholesale and warehouse workers. In my childhood I

took little interest in his work and unions as a whole, but later in

life I realized how profoundly I was influenced by his teachings and

his example.

I dropped out of college during my sophomore year. In November 1965, I

received my “Greetings From Uncle Sam”—the actual wording of

U.S. Army induction orders at the time.

I was drafted in December and assigned to a Fort Hood, Texas, signal

battalion for basic training. In the spring of 1966, I began my

advanced training as a signal unit switchboard operator at Fort

Gordon, outside Augusta, Georgia. There I joined a study group of

seven GIs who had questions about our nation’s involvement in

Vietnam and Southeast Asia.

I needed justification for taking up arms against a nation of farmers

and peasants 10,000 miles from our shores. The training films we were

forced to watch in basic offended more than informed. I also found

offensive the derogatory terms applied to the Vietnamese people and

others from Southeast Asia.

Two of the members of the Fort Gordon study group had been political

activists. They provided most of the reading material. They also

arranged meetings with local anti-war groups and members of the

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, an early opponent of the

war and led at the time by Stokely Carmichael.

Reading the literature, especially from SNCC, taught me that as a

Black American, my battleground was at home, not in Southeast Asia. I

also learned that Black soldiers were disproportionately assigned to

the infantry and were dying at a rate far above our percentage in the

country.

I read that Ho Chin Minh, the revered leader of Vietnam’s

anti-colonial independence movement, lived in Harlem in the 1920s and

wrote a pamphlet denouncing the lynching of Black Americans. This

helped to endear me to Uncle Ho, as he was affectionately called, and

to the plight of the Vietnamese people who had fought for decades for

the right to self-determination.

During the summer of 1966, I and two other members of the study group,

Dennis Mora and David Samas, announced that we would not comply with

our orders to serve in Vietnam. “We refuse to take part in an

illegal, immoral and unjust war,” our joint statement read.

The support of our families, friends, and the growing anti-war

movement helped us stand our ground and sustained us during our 28

months in prison. The growth of the opposition outside and within the

military convinced us that making our opposition public had helped to

build the movement.

I took special pride in heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali’s refusal

to step forward for induction and his contention, “I will not go

10,000 miles to help kill innocent Brown people.”

Weeks earlier, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had delivered his “Beyond

Vietnam” address at Riverside Church, in which he called for an end

to the war and a “radical revolution of values.” He also said that

the United States was “the greatest purveyor of violence in the

world today.”

The corporate media and even organizations like the NAACP condemned

him, arguing that Dr. King should not link disparate issues—war and

civil rights. In his “Where Do We Go From Here?” speech in Atlanta

later that year, Dr. King said, “We must see now that the evils of

racism, exploitation, and militarism are all tied together. And you

can’t get rid of one without getting rid of the other.”

Dr. King connected the dots. The problem was systemic. Years later, I

would better understand the connections. I became a labor journalist

because I wanted to help other working people connect the dots and see

the intersection of the evils.

A clearer understanding of our common cause, I felt, would knock down

walls, build bridges, and move us closer to a more equal and humane

society. We’ve alternately taken some steps forward and backward. A

major setback has been the decline of the labor movement, although the

stirrings in recent years are encouraging.

Today, we have entered the darkest period in my lifetime. Far-right

authoritarianism (some call it fascism) has arrived on the heels of a

racist campaign of otherism. Our nation is now controlled by an

oligarchy headed by the world’s richest man—a child of apartheid

South Africa.

The current president is not the first to stoke racism and xenophobia,

but he has taken it the furthest in generations. A nation founded on

the exclusion and removal of its Indigenous people and erected on the

backs of enslaved Africans helped write the book on racism and

othering.

The guardians of our nation’s vaunted exceptionalism would have us

believe that our borders and way of life are threatened by immigrants

of color. Like immigrants of earlier generations, they are simply

seeking a better life for themselves and their children. Many have

fled to escape governments and conditions for which U.S.

administrations are responsible.

“We are here because you were there,” say immigrants when

questioned about why they left their place of birth.

The process of othering is not just about who gets to be defined as

the true or real American. And it’s not simply about race. It’s

about tightening the grip of the corporate class and billionaires. As

Dr. King stressed, our fight is against the triple evils of racism,

economic exploitation, and militarism. One can’t be fully addressed

without addressing the others.

To keep the world safe for multinational corporations, the United

States commands roughly 800 military bases in some 80 countries around

the world. That enormous military presence also enriches the military

industrial complex that the late Republican President Dwight

Eisenhower warned our nation about in his 1961 farewell address.

Militarism together with the climate catastrophe are the chief factors

that have moved the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists’ Doomsday Clock to

89 seconds before midnight, indicating how close we are to destroying

the world.

A bedfellow of today’s militarism is Christian nationalism. _The

New York Times_ reported that Speaker of the House Mike Johnson, a

Louisiana Republican, is the first Christian nationalist to hold that

post.

Many Christian nationalists are Christian Zionists, who believe the

restoration of Jewish people to Israel is a prerequisite for the

second coming of Christ. That helps to explain the absence of

sufficient outrage over the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza.

The Red Scare of the last century has been replaced by the war on

terrorism. Today Muslims, Arabs, and Palestinians are the main

targets. Also in the crosshairs are immigrants of color, especially

students who oppose the policies of the Israeli administration.

The Trump administration has invoked the Alien Enemies Act to harass,

silence, and kidnap immigrant students and workers. In April, the

Supreme Court lifted a restraining order that had prevented mass

deportations. Justice Sonia Sotomayor dissented, saying that “not

only non-citizens could be taken off the streets, forced into planes

and confined to foreign prisons with no opportunity for redress if

judicial review is denied unlawfully before removal.”

The United States has been a flawed democracy from its inception. But

today we are threatened with the loss of our remaining rights.

Our only choice is to fight back—including us seniors—by forming

alliances and coalitions that are even broader and deeper than those

that helped to end the war against the Vietnamese people. In this

fight back, while respecting differences, there is no them or other,

only us.

_JJ Johnson is one of the Fort Hood 3, who in 1966 were the first U.S.

soldiers to publicly refuse to serve in Vietnam. He is a retired labor

journalist._

_The Washington Spectator [[link removed]] is

an independent, progressive and reader-supported journal of politics

and the arts published each month in print, and updated daily online

at washingtonspectator.org [[link removed]]. Click

here to contribute to The Washington Spectator

[[link removed]]._

* Ford Hood 3

[[link removed]]

* Anti-Vietnam War movement

[[link removed]]

* Militarism

[[link removed]]

* Christian nationalism

[[link removed]]

* Solidarity

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

INTERPRET THE WORLD AND CHANGE IT

Submit via web

[[link removed]]

Submit via email

Frequently asked questions

[[link removed]]

Manage subscription

[[link removed]]

Visit xxxxxx.org

[[link removed]]

Twitter [[link removed]]

Facebook [[link removed]]

[link removed]

To unsubscribe, click the following link:

[link removed]

A VIETNAM STORY: FROM OTHERING TO SOLIDARITY

[[link removed]]

JJ Johnson

April 29, 2025

Washington Spectator

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

_ Fifty years after the end of the Vietnam War, JJ Johnson reflects

on the journey that led him, along with two fellow Fort Hood soldiers,

to refuse orders to Vietnam and on our situation today, "the darkest

period in my lifetime." _

Private Dennis Mora, Private First Class David Samas and Private

First Class JJ Johnson (left to right) were the first were the first

U.S. soldiers to publicly refuse deployment to Vietnam in 1966,

In my 1950s East Harlem household, solidarity was akin to religion. In

my family’s two-bedroom tenement, all were welcome, irrespective of

race, ethnicity, religious belief, or sexual orientation. As a child,

five-syllable words like _solidarity_ were not in my vocabulary, but

fairness and kindness were.

Although we were poor, my parents—both of whom were orphaned for

parts of their childhoods—always found room in our two-bedroom

walk-up for relatives and friends who needed a place to stay.

My dad was also a trade union activist in District 65, then a small

scrappy union of wholesale and warehouse workers. In my childhood I

took little interest in his work and unions as a whole, but later in

life I realized how profoundly I was influenced by his teachings and

his example.

I dropped out of college during my sophomore year. In November 1965, I

received my “Greetings From Uncle Sam”—the actual wording of

U.S. Army induction orders at the time.

I was drafted in December and assigned to a Fort Hood, Texas, signal

battalion for basic training. In the spring of 1966, I began my

advanced training as a signal unit switchboard operator at Fort

Gordon, outside Augusta, Georgia. There I joined a study group of

seven GIs who had questions about our nation’s involvement in

Vietnam and Southeast Asia.

I needed justification for taking up arms against a nation of farmers

and peasants 10,000 miles from our shores. The training films we were

forced to watch in basic offended more than informed. I also found

offensive the derogatory terms applied to the Vietnamese people and

others from Southeast Asia.

Two of the members of the Fort Gordon study group had been political

activists. They provided most of the reading material. They also

arranged meetings with local anti-war groups and members of the

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, an early opponent of the

war and led at the time by Stokely Carmichael.

Reading the literature, especially from SNCC, taught me that as a

Black American, my battleground was at home, not in Southeast Asia. I

also learned that Black soldiers were disproportionately assigned to

the infantry and were dying at a rate far above our percentage in the

country.

I read that Ho Chin Minh, the revered leader of Vietnam’s

anti-colonial independence movement, lived in Harlem in the 1920s and

wrote a pamphlet denouncing the lynching of Black Americans. This

helped to endear me to Uncle Ho, as he was affectionately called, and

to the plight of the Vietnamese people who had fought for decades for

the right to self-determination.

During the summer of 1966, I and two other members of the study group,

Dennis Mora and David Samas, announced that we would not comply with

our orders to serve in Vietnam. “We refuse to take part in an

illegal, immoral and unjust war,” our joint statement read.

The support of our families, friends, and the growing anti-war

movement helped us stand our ground and sustained us during our 28

months in prison. The growth of the opposition outside and within the

military convinced us that making our opposition public had helped to

build the movement.

I took special pride in heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali’s refusal

to step forward for induction and his contention, “I will not go

10,000 miles to help kill innocent Brown people.”

Weeks earlier, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had delivered his “Beyond

Vietnam” address at Riverside Church, in which he called for an end

to the war and a “radical revolution of values.” He also said that

the United States was “the greatest purveyor of violence in the

world today.”

The corporate media and even organizations like the NAACP condemned

him, arguing that Dr. King should not link disparate issues—war and

civil rights. In his “Where Do We Go From Here?” speech in Atlanta

later that year, Dr. King said, “We must see now that the evils of

racism, exploitation, and militarism are all tied together. And you

can’t get rid of one without getting rid of the other.”

Dr. King connected the dots. The problem was systemic. Years later, I

would better understand the connections. I became a labor journalist

because I wanted to help other working people connect the dots and see

the intersection of the evils.

A clearer understanding of our common cause, I felt, would knock down

walls, build bridges, and move us closer to a more equal and humane

society. We’ve alternately taken some steps forward and backward. A

major setback has been the decline of the labor movement, although the

stirrings in recent years are encouraging.

Today, we have entered the darkest period in my lifetime. Far-right

authoritarianism (some call it fascism) has arrived on the heels of a

racist campaign of otherism. Our nation is now controlled by an

oligarchy headed by the world’s richest man—a child of apartheid

South Africa.

The current president is not the first to stoke racism and xenophobia,

but he has taken it the furthest in generations. A nation founded on

the exclusion and removal of its Indigenous people and erected on the

backs of enslaved Africans helped write the book on racism and

othering.

The guardians of our nation’s vaunted exceptionalism would have us

believe that our borders and way of life are threatened by immigrants

of color. Like immigrants of earlier generations, they are simply

seeking a better life for themselves and their children. Many have

fled to escape governments and conditions for which U.S.

administrations are responsible.

“We are here because you were there,” say immigrants when

questioned about why they left their place of birth.

The process of othering is not just about who gets to be defined as

the true or real American. And it’s not simply about race. It’s

about tightening the grip of the corporate class and billionaires. As

Dr. King stressed, our fight is against the triple evils of racism,

economic exploitation, and militarism. One can’t be fully addressed

without addressing the others.

To keep the world safe for multinational corporations, the United

States commands roughly 800 military bases in some 80 countries around

the world. That enormous military presence also enriches the military

industrial complex that the late Republican President Dwight

Eisenhower warned our nation about in his 1961 farewell address.

Militarism together with the climate catastrophe are the chief factors

that have moved the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists’ Doomsday Clock to

89 seconds before midnight, indicating how close we are to destroying

the world.

A bedfellow of today’s militarism is Christian nationalism. _The

New York Times_ reported that Speaker of the House Mike Johnson, a

Louisiana Republican, is the first Christian nationalist to hold that

post.

Many Christian nationalists are Christian Zionists, who believe the

restoration of Jewish people to Israel is a prerequisite for the

second coming of Christ. That helps to explain the absence of

sufficient outrage over the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza.

The Red Scare of the last century has been replaced by the war on

terrorism. Today Muslims, Arabs, and Palestinians are the main

targets. Also in the crosshairs are immigrants of color, especially

students who oppose the policies of the Israeli administration.

The Trump administration has invoked the Alien Enemies Act to harass,

silence, and kidnap immigrant students and workers. In April, the

Supreme Court lifted a restraining order that had prevented mass

deportations. Justice Sonia Sotomayor dissented, saying that “not

only non-citizens could be taken off the streets, forced into planes

and confined to foreign prisons with no opportunity for redress if

judicial review is denied unlawfully before removal.”

The United States has been a flawed democracy from its inception. But

today we are threatened with the loss of our remaining rights.

Our only choice is to fight back—including us seniors—by forming

alliances and coalitions that are even broader and deeper than those

that helped to end the war against the Vietnamese people. In this

fight back, while respecting differences, there is no them or other,

only us.

_JJ Johnson is one of the Fort Hood 3, who in 1966 were the first U.S.

soldiers to publicly refuse to serve in Vietnam. He is a retired labor

journalist._

_The Washington Spectator [[link removed]] is

an independent, progressive and reader-supported journal of politics

and the arts published each month in print, and updated daily online

at washingtonspectator.org [[link removed]]. Click

here to contribute to The Washington Spectator

[[link removed]]._

* Ford Hood 3

[[link removed]]

* Anti-Vietnam War movement

[[link removed]]

* Militarism

[[link removed]]

* Christian nationalism

[[link removed]]

* Solidarity

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

[[link removed]]

*

*

[[link removed]]

INTERPRET THE WORLD AND CHANGE IT

Submit via web

[[link removed]]

Submit via email

Frequently asked questions

[[link removed]]

Manage subscription

[[link removed]]

Visit xxxxxx.org

[[link removed]]

Twitter [[link removed]]

Facebook [[link removed]]

[link removed]

To unsubscribe, click the following link:

[link removed]

Message Analysis

- Sender: Portside

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: n/a

- Office: n/a