Email

Why do some people prosper, yet others fail? - Update from your favorite think tank

| From | Douglas Carswell <[email protected]> |

| Subject | Why do some people prosper, yet others fail? - Update from your favorite think tank |

| Date | June 10, 2023 12:44 PM |

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

Links have been removed from this email. Learn more in the FAQ.

View this email in your browser ([link removed])

Dear Jack,

Economic output per person is seven times higher on the American side of the US-Mexico border than on the other. Why? How come the average Canadian is twelve times richer than the average Moroccan, despite both countries have similar size populations?

We are often invited to believe that a society’s relative success has a lot to do with its geography or climate. I disagree.

There are plenty of resource-rich countries in Africa, blessed in every imaginable way by geography and climate, that still produce only grinding poverty. Conversely, there are plenty of resource-poor places, such as Japan or Iceland, that prosper.

Much more important than a country’s natural resources is its public policy.

If property rights are insecure, power arbitrary and taxes high, a society will remain poor. If, on the other hand, people are free to spend more of their own money and make their own choices for themselves and their families, society overall will thrive.

Perhaps the single best illustration of this is Korea. Since the end of the Korean war, the Korean peninsula has been divided. North Korea has been run by a communist dictatorship, under which there are no property rights and rules for everything, including what you can wear. South Korea, especially since the 1980s, is an open, free market society, with relatively low taxes and light regulation.

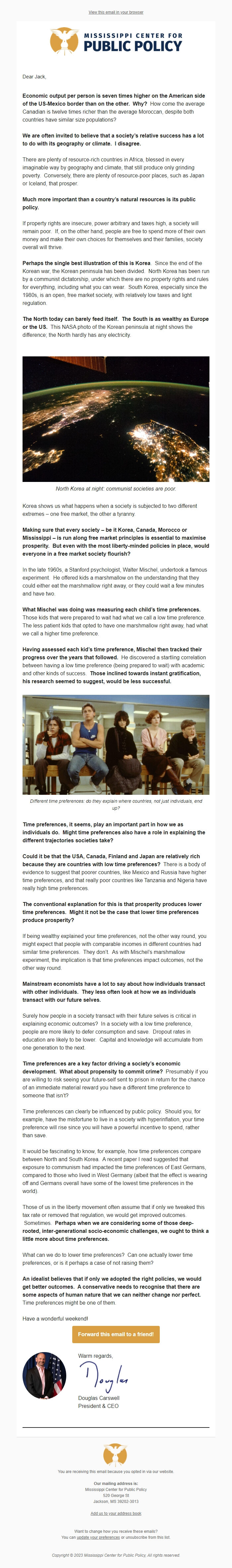

The North today can barely feed itself. The South is as wealthy as Europe or the US. This NASA photo of the Korean peninsula at night shows the difference; the North hardly has any electricity.

North Korea at night: communist societies are poor.

Korea shows us what happens when a society is subjected to two different extremes – one free market, the other a tyranny.

Making sure that every society – be it Korea, Canada, Morocco or Mississippi – is run along free market principles is essential to maximise prosperity. But even with the most liberty-minded policies in place, would everyone in a free market society flourish?

In the late 1960s, a Stanford psychologist, Walter Mischel, undertook a famous experiment. He offered kids a marshmallow on the understanding that they could either eat the marshmallow right away, or they could wait a few minutes and have two.

What Mischel was doing was measuring each child’s time preferences. Those kids that were prepared to wait had what we call a low time preference. The less patient kids that opted to have one marshmallow right away, had what we call a higher time preference.

Having assessed each kid’s time preference, Mischel then tracked their progress over the years that followed. He discovered a startling correlation between having a low time preference (being prepared to wait) with academic and other kinds of success. Those inclined towards instant gratification, his research seemed to suggest, would be less successful.

Different time preferences: do they explain where countries, not just individuals, end up?

Time preferences, it seems, play an important part in how we as individuals do. Might time preferences also have a role in explaining the different trajectories societies take?

Could it be that the USA, Canada, Finland and Japan are relatively rich because they are countries with low time preferences? There is a body of evidence to suggest that poorer countries, like Mexico and Russia have higher time preferences, and that really poor countries like Tanzania and Nigeria have really high time preferences.

The conventional explanation for this is that prosperity produces lower time preferences. Might it not be the case that lower time preferences produce prosperity?

If being wealthy explained your time preferences, not the other way round, you might expect that people with comparable incomes in different countries had similar time preferences. They don’t. As with Mischel’s marshmallow experiment, the implication is that time preferences impact outcomes, not the other way round.

Mainstream economists have a lot to say about how individuals transact with other individuals. They less often look at how we as individuals transact with our future selves.

Surely how people in a society transact with their future selves is critical in explaining economic outcomes? In a society with a low time preference, people are more likely to defer consumption and save. Dropout rates in education are likely to be lower. Capital and knowledge will accumulate from one generation to the next.

Time preferences are a key factor driving a society’s economic development. What about propensity to commit crime? Presumably if you are willing to risk seeing your future-self sent to prison in return for the chance of an immediate material reward you have a different time preference to someone that isn’t?

Time preferences can clearly be influenced by public policy. Should you, for example, have the misfortune to live in a society with hyperinflation, your time preference will rise since you will have a powerful incentive to spend, rather than save.

It would be fascinating to know, for example, how time preferences compare between North and South Korea. A recent paper I read suggested that exposure to communism had impacted the time preferences of East Germans, compared to those who lived in West Germany (albeit that the effect is wearing off and Germans overall have some of the lowest time preferences in the world).

Those of us in the liberty movement often assume that if only we tweaked this tax rate or removed that regulation, we would get improved outcomes. Sometimes. Perhaps when we are considering some of those deep-rooted, inter-generational socio-economic challenges, we ought to think a little more about time preferences.

What can we do to lower time preferences? Can one actually lower time preferences, or is it perhaps a case of not raising them?

An idealist believes that if only we adopted the right policies, we would get better outcomes. A conservative needs to recognise that there are some aspects of human nature that we can neither change nor perfect. Time preferences might be one of them.

Have a wonderful weekend!

Forward this email to a friend! ([link removed])

Warm regards,

Douglas Carswell

President & CEO

============================================================

You are receiving this email because you opted in via our website.

Our mailing address is:

Mississippi Center for Public Policy

520 George St

Jackson, MS 39202-3013

USA

Want to change how you receive these emails?

You can ** update your preferences ([link removed])

or ** unsubscribe from this list ([link removed])

.

Copyright © 2023 Mississippi Center for Public Policy, All rights reserved.

Dear Jack,

Economic output per person is seven times higher on the American side of the US-Mexico border than on the other. Why? How come the average Canadian is twelve times richer than the average Moroccan, despite both countries have similar size populations?

We are often invited to believe that a society’s relative success has a lot to do with its geography or climate. I disagree.

There are plenty of resource-rich countries in Africa, blessed in every imaginable way by geography and climate, that still produce only grinding poverty. Conversely, there are plenty of resource-poor places, such as Japan or Iceland, that prosper.

Much more important than a country’s natural resources is its public policy.

If property rights are insecure, power arbitrary and taxes high, a society will remain poor. If, on the other hand, people are free to spend more of their own money and make their own choices for themselves and their families, society overall will thrive.

Perhaps the single best illustration of this is Korea. Since the end of the Korean war, the Korean peninsula has been divided. North Korea has been run by a communist dictatorship, under which there are no property rights and rules for everything, including what you can wear. South Korea, especially since the 1980s, is an open, free market society, with relatively low taxes and light regulation.

The North today can barely feed itself. The South is as wealthy as Europe or the US. This NASA photo of the Korean peninsula at night shows the difference; the North hardly has any electricity.

North Korea at night: communist societies are poor.

Korea shows us what happens when a society is subjected to two different extremes – one free market, the other a tyranny.

Making sure that every society – be it Korea, Canada, Morocco or Mississippi – is run along free market principles is essential to maximise prosperity. But even with the most liberty-minded policies in place, would everyone in a free market society flourish?

In the late 1960s, a Stanford psychologist, Walter Mischel, undertook a famous experiment. He offered kids a marshmallow on the understanding that they could either eat the marshmallow right away, or they could wait a few minutes and have two.

What Mischel was doing was measuring each child’s time preferences. Those kids that were prepared to wait had what we call a low time preference. The less patient kids that opted to have one marshmallow right away, had what we call a higher time preference.

Having assessed each kid’s time preference, Mischel then tracked their progress over the years that followed. He discovered a startling correlation between having a low time preference (being prepared to wait) with academic and other kinds of success. Those inclined towards instant gratification, his research seemed to suggest, would be less successful.

Different time preferences: do they explain where countries, not just individuals, end up?

Time preferences, it seems, play an important part in how we as individuals do. Might time preferences also have a role in explaining the different trajectories societies take?

Could it be that the USA, Canada, Finland and Japan are relatively rich because they are countries with low time preferences? There is a body of evidence to suggest that poorer countries, like Mexico and Russia have higher time preferences, and that really poor countries like Tanzania and Nigeria have really high time preferences.

The conventional explanation for this is that prosperity produces lower time preferences. Might it not be the case that lower time preferences produce prosperity?

If being wealthy explained your time preferences, not the other way round, you might expect that people with comparable incomes in different countries had similar time preferences. They don’t. As with Mischel’s marshmallow experiment, the implication is that time preferences impact outcomes, not the other way round.

Mainstream economists have a lot to say about how individuals transact with other individuals. They less often look at how we as individuals transact with our future selves.

Surely how people in a society transact with their future selves is critical in explaining economic outcomes? In a society with a low time preference, people are more likely to defer consumption and save. Dropout rates in education are likely to be lower. Capital and knowledge will accumulate from one generation to the next.

Time preferences are a key factor driving a society’s economic development. What about propensity to commit crime? Presumably if you are willing to risk seeing your future-self sent to prison in return for the chance of an immediate material reward you have a different time preference to someone that isn’t?

Time preferences can clearly be influenced by public policy. Should you, for example, have the misfortune to live in a society with hyperinflation, your time preference will rise since you will have a powerful incentive to spend, rather than save.

It would be fascinating to know, for example, how time preferences compare between North and South Korea. A recent paper I read suggested that exposure to communism had impacted the time preferences of East Germans, compared to those who lived in West Germany (albeit that the effect is wearing off and Germans overall have some of the lowest time preferences in the world).

Those of us in the liberty movement often assume that if only we tweaked this tax rate or removed that regulation, we would get improved outcomes. Sometimes. Perhaps when we are considering some of those deep-rooted, inter-generational socio-economic challenges, we ought to think a little more about time preferences.

What can we do to lower time preferences? Can one actually lower time preferences, or is it perhaps a case of not raising them?

An idealist believes that if only we adopted the right policies, we would get better outcomes. A conservative needs to recognise that there are some aspects of human nature that we can neither change nor perfect. Time preferences might be one of them.

Have a wonderful weekend!

Forward this email to a friend! ([link removed])

Warm regards,

Douglas Carswell

President & CEO

============================================================

You are receiving this email because you opted in via our website.

Our mailing address is:

Mississippi Center for Public Policy

520 George St

Jackson, MS 39202-3013

USA

Want to change how you receive these emails?

You can ** update your preferences ([link removed])

or ** unsubscribe from this list ([link removed])

.

Copyright © 2023 Mississippi Center for Public Policy, All rights reserved.

Message Analysis

- Sender: Mississippi Center for Public Policy

- Political Party: n/a

- Country: United States

- State/Locality: Mississippi

- Office: n/a

-

Email Providers:

- MailChimp